June 8th, 1945. Camp Gruber, Oklahoma. The war was over. Germany had surrendered and 15-year-old Klaus Becker was supposed to be going home. Instead, he stood gripping a chainlink fence, knuckles white, staring out at the endless American prairie, trying not to panic at the thought of leaving.

A guard passed behind him, boots crunching on gravel. Klouse didn’t turn. He had been standing there for nearly 2 hours, frozen in place, because for the first time in his life, he was afraid of freedom. Most prisoners begged to be released. Klouse was bracing himself for something worse. He was bracing himself to be sent back, back to Hamburg, where his home was rubble, his father was dead, his mother was missing, and the future waiting for him smelled like ash and hunger.

back to a country that had taken everything from him, including his childhood. Here, behind barbed wire in Oklahoma, he had food, he had safety, he had school, and he had something Germany no longer offered him, a future. Before we dive deeper into this story, if you’re fascinated by the untold human truths of World War II, hit that like button and subscribe to the channel.

Drop a comment below telling us where you’re watching from. Your support keeps these forgotten stories alive. Now, let’s continue. The realization had hit him three nights earlier, lying in his bunk, staring at the ceiling of the barracks. He had imagined returning to Hamburg. The city he remembered no longer existed.

The house where he’d grown up was rubble. His father was dead. His mother, last he heard, was somewhere in the Soviet zone, and the future waiting for him. There was a wasteland of hunger, ruin, and judgment. Here in Oklahoma, there were three meals a day. There was safety. There was a future that didn’t smell like ash.

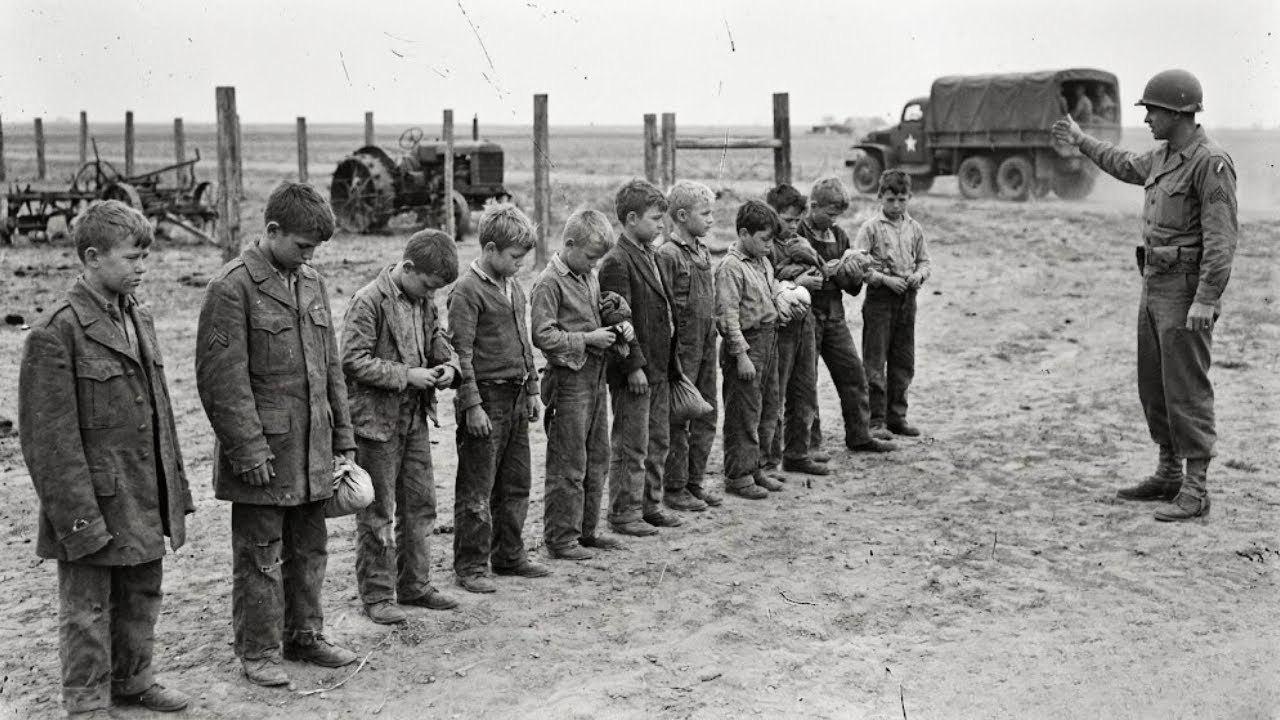

The boys had arrived at Camp Gruber in the winter of 1945. They were part of a group the Americans called Hitler’s children, the youngest prisoners of war ever held on US soil. Most were between 13 and 16 years old. Some had been conscripted into the Vermacht in the final months of the war. Others had served in the Vulks term the desperate home guard Hitler had cobbled together from old men and boys.

They had fought in the Battle of the Bulge. They had manned anti-aircraft guns in Berlin. They had dug trenches in the frozen mud of the Rhineland. And when the Americans captured them, they were still wearing uniforms three sizes too large. Their helmets slipped over their eyes. Their rifles were taller than they were.

The US Army didn’t know what to do with them. They couldn’t be tried as soldiers. They were children, but they couldn’t be released either. Many had no homes to return to, no families, no nation that wanted them back. So, they were sent to camps across the American heartland. camps in Texas, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Camp Gruber near Muscogi became home to one of the largest groups. By April 1945, over 200 German child soldiers were housed there. They lived in wooden barracks. They ate in mesh halls. They attended makeshift schools run by American officers and German immigrants. And slowly, something unexpected began to happen.

They started to heal. Klaus had been conscripted in December 1944. He was 14. His father, a factory foreman in Hamburg, had been killed in an air raid the year before. His older brother had died at Stalingrad. When the Vulk Strerm came calling, Clauser’s mother had begged them to leave her last son alone. They took him anyway.

They gave him a rifle and told him to defend the fatherland. He didn’t fire a single shot in anger. His unit surrendered to the Americans near Aken in February 1,945. The G as who captured them looked more confused than angry. One soldier, a kid from Iowa barely older than Klouse himself, had offered him a cigarette. Klouse didn’t smoke, but he took it anyway.

It was the first kindness he’d received in months. The train ride to America had taken 3 weeks. Klouse and the other boys were packed into the hold of a Liberty ship. The Atlantic was gray and endless. Some of the boys were seasick the entire voyage. Others spent their time playing cards or telling stories.

One boy, a 15-year-old from Munich named Otto, swore he would escape the moment they landed. He would steal a boat and sail back to Germany. He would find his family. He would rebuild. But when they arrived at Camp Gruber, something changed. The prairie stretched out in every direction, vast and quiet. There were no bombed out buildings, no sirens, no fear.

The guards were firm, but not cruel. The food was plain but plentiful, and for the first time in years, the boys were allowed to be boys again. The camp commander, Colonel William Hastings, was a tall man with green hair and a calm demeanor. He had served in the Great War and had seen enough death to last a lifetime.

When the first group of child prisoners arrived, he gathered his officers and gave them a single order. Treat them like kids, not like enemies. It wasn’t popular. Some of the guards had lost brothers in France or the Pacific. They didn’t want to show mercy to German boys who had worn the swastika.

But Hastings was unmoved. These kids didn’t start this war, he said. And they won’t end it by rotting in a camp. Teach them something. Give them a future. So the Americans set up a school. A German immigrate named Dr. Friedrich Lana, a professor who had fled Berlin in 1938, was hired to run it.

He taught history, mathematics, and English. He also taught something the boys had never learned in Germany, critical thinking. He asked them questions. He made them argue. He showed them newspapers from across the world. And slowly, piece by piece, he began to dismantle the lies they had been fed. At first, the boys resisted.

Klaus remembered the day Dr. L told them about the concentration camps, the ovens, the mass graves, the 6 million. Klaus had refused to believe it. He had stood up in class and called it propaganda. Dr. Lang had looked at him with sadness, not anger. I understand, he said, but the truth doesn’t care whether you believe it.

That night, Claus couldn’t sleep. He thought about the stories his father used to tell, about the pride of Germany, about the glory of the Reich, and he wondered how much of it had been a lie. By spring, the boys had settled into a routine. They woke at 6. They did chores. They attended classes.

They played soccer on a dirt field behind the barracks. The Americans even organized a small library stocked with German and English books. Klouse spent hours there reading everything he could. He discovered Mark Twain. He discovered Jack London and he began to imagine a life beyond the war. But then the war ended and everything changed.

May 8th, 1945, the announcement came over the loudspeakers. Germany had surrendered unconditionally. The Third Reich was no more. The boys gathered in the mess hall to hear the news. Some wept. Some sat in stunned silence. One boy, a 16-year-old named Hans, let out a cheer. A guard told him to shut up.

Hans apologized, but Klaus saw the look in his eyes. Relief. For weeks, the boys didn’t know what would happen to them. The war was over, but their future was uncertain. Would they be sent home? Would they be kept in America? Would they be punished? The rumors flew. Some boys heard they would be sent to work camps in France.

Others heard they would be adopted by American families. No one knew the truth. Klaus began to dread the day he would be put on a ship back to Germany. He tried to picture it. Standing in the ruins of Hamburg, searching for his mother, starting over in a country that had lost everything.

And the more he thought about it, the less he wanted to go. One evening he spoke to Dr. Longa. “What if I don’t want to leave?” he asked. Dr. Longi raised an eyebrow. “What do you mean?” “I mean, what if I want to stay here in America?” Dr. Lang sighed. He sat down and motioned for Claus to do the same. Klaus, I understand. Believe me, I do.

But you’re a prisoner of war. You don’t get to choose. But the war is over. Yes. and now you have to go home and help rebuild. Klaus shook his head. There’s nothing to rebuild. My city is gone. My family is gone. What am I going home to? Dr. Lang didn’t answer right away. He looked out the window at the Oklahoma prairie.

I asked myself the same question in 1938, he said quietly. And I chose to leave, but you’re not me. You’re 15. You have a lifetime ahead of you. Don’t run from your country because it’s broken. Stay and fix it. But Klaus wasn’t convinced, and he wasn’t alone. By June, nearly 40 of the boys at Camp Gruber, had expressed a desire to stay in America.

Some wanted to finish their education. Others wanted to work. A few, like Klouse, simply didn’t want to face the ruin waiting for them across the ocean. They wrote letters to the camp commander. They petitioned the Red Cross. They begged for asylum. The American authorities were baffled. The Geneva Convention required the repatriation of all prisoners of war once hostilities ended.

But these boys weren’t ordinary posts. They were children. And their situation was unprecedented. Washington sent lawyers and diplomats to review the cases. Churches and civic groups in Oklahoma offered to sponsor some of the boys. Local families moved by their stories volunteered to take them in. But the army was firm.

The boys had to go home. Orders were orders. Klouse heard the news on a humid afternoon in late June. Repatriation would begin in 2 weeks. All prisoners would be returned to Germany by the end of August. He felt something inside him crack. That night he lay in his bunk and stared at the ceiling. He [clears throat] thought about running.

He thought about hiding, but he knew it was useless. The next morning, he went back to the fence. He stood there for hours, gripping the wire, staring at the prairie. A guard named Corporal Miller walked over. “You okay, kid?” Klaus didn’t answer. “Look,” Miller said. “I know it’s hard, but you’ll be all right.

Germany’s going to need guys like you.” Klouse finally looked at him. “What if I don’t want to go?” Miller hesitated. “Doesn’t matter what you want. It’s what has to happen. Why? Because that’s where you belong. Klouse shook his head. I don’t belong anywhere. July 1945. The barracks at Camp Gruber grew quieter.

The boys packed their few belongings. They said goodbye to the teachers who had tried to show them a different world. They shook hands with the guards who had treated them with unexpected kindness. And one by one they boarded trucks that would take them to trains that would take them to ships that would carry them back across the ocean.

Klouse was in the last group to leave. On his final night he walked to the fence one more time. The sun was setting over the prairie. The sky was orange and gold. The air smelled like dry grass and dust. He thought about his mother. He wondered if she was still alive. He wondered if she would even recognize him. Dr.

Longa found him there. You ready? He asked. Klouse didn’t answer. You know, Dr. Lang said, “I left Germany because I had to. You’re leaving because you have to. But maybe one day you’ll come back here because you want to, and that will mean something.” Klaus nodded. He didn’t believe it, but he nodded anyway. The next morning, the trucks rolled out.

Klaus watched through the rear window as Camp Gruber disappeared into the distance. The barracks, the fence, the field where they’d played soccer, all of it fading into the flat Oklahoma horizon. He felt like he was leaving the only safe place he’d ever known. The ship that carried them back was called the SS Marine Raven.

It was crowded and cold. The boys slept in hammocks stacked three high. The crossing took 12 days. When they finally arrived at Bremerhav, the port was a wasteland. Cranes lay toppled in the water. Buildings were hollowed out by fire. The air smelled like salt and smoke and rot. Claus stepped off the ship and onto German soil for the first time in 7 months.

He felt nothing, no relief, no joy, just emptiness. He was processed by British authorities and given a travel pass to Hamburg. The train ride took 6 hours. The windows were cracked, the seats were torn, the countryside rolled past in shades of gray and brown, farm houses with missing roofs, fields pocked with craters, forests stripped bare by artillery.

When he reached Hamburg, he almost didn’t recognize it. Entire neighborhoods were gone. The streets he used to walk were now paths through rubble. He found the address where his family’s apartment had been. It was a pile of bricks. He stood there for a long time staring at the ruins. A woman walking past stopped and asked if he was looking for someone.

Klouse told her his mother’s name. The woman shook her head. I don’t know her, but you can check the refugee lists at the church. Klouse went to the church. The lists were pinned to a board in the vestibule. Thousands of names. He scanned them for an hour. He didn’t find his mother. He found his grandmother.

She was living in a displaced person’s camp near Lubec. He took a train there the next day. She didn’t recognize him at first. He had left as a boy. He returned as something else. When he told her who he was, she wept. She held him and asked him where he’d been. He told her. He told her about Oklahoma, about the school, about the fence.

And when he was done, she looked [clears throat] at him with hollow eyes and said, “You should have stayed.” Klouse spent the next year trying to rebuild. He worked odd jobs. He cleared rubble. He helped rebuild walls. He attended night school and learned a trade. And slowly, painfully, he began to carve out a life. But he never stopped thinking about Oklahoma, about the prairie, about the freedom he’d felt standing at that fence.

In 1947, he applied for a visa to return to the United States. It was denied. He applied again in 1949, denied again. In 1952, the rules changed. West Germany was rebuilding. Relations with America were warming. Klouse applied a third time. This time it was approved. He sailed back to America in the spring of 1953.

He was 22 years old. He settled in Tulsa, less than 50 mi from Camp Gruber. He got a job in a factory. He learned English. He married a local girl named Mary. They had two children. And every year on June 8th, he drove out to the site where Camp Gruber had been. The barracks were long gone.

The fence had been torn down, but he stood there anyway, remembering the boy he’d been and the man he’d become. Claus was not the only one. Of the 200 child soldiers who passed through Camp Gruber, at least 30 eventually returned to the United States. Some came as immigrants, others as students, a few came as tourists and never left.

They built lives here quietly and deliberately. They found work, learned the language, married, raised families. Over time, they became Americans in every way that mattered. But none of them ever forgot the strange, painful summer of 1945, the summer they were prisoners who didn’t want to be freed. It was a story that sat uneasily at the edges of history.

Historians rarely mentioned them because their experience refused to fit into clean lines of victory and defeat. They were neither heroes nor villains. They were children caught inside a war they barely understood, shaped by propaganda and fear, saved by a country they had been taught to hate. Liberation came with confusion instead of joy.

Freedom meant being sent back across an ocean to a homeland that had been shattered, altered, and in many cases erased entirely. For years, their memories lived mostly in silence. Yet, when given a choice later in life, when paperwork and patience finally opened a door, many of them chose America, not out of politics or ideology, but because this was where their lives had taken root.

This was where they had been allowed to grow into themselves rather than into what history demanded of them. Because sometimes home isn’t where you’re born. Sometimes it’s where you’re safe. Sometimes it’s where you’re seen. Sometimes it’s simply where you’re allowed to become who you were meant to be.

Klaus Becker died in Tulsa in 1998 at the age of 67. The service was small and quiet, attended by family, a few friends, and neighbors who knew him as a gentle man with a soft accent and a careful way of speaking. To most of them, Klouse was simply a husband, a father, a co-worker, someone who had lived an unremarkable American life.

Only fragments of his earlier years ever surfaced, usually in brief comments he never lingered on. After the funeral, his son sat alone and sorted through his father’s belongings. There were letters, old documents, a warm wallet whose leather had thinned with age. Inside it, tucked behind expired cards and folded bills, he found a photograph Klaus had carried for decades.

The picture was faded, its corners rounded and softened from being handled again and again, as if it had been taken out often, then carefully returned. The image itself was simple. A chainlink fence stretched across an empty prairie, dividing foreground from horizon. Beyond the fence, the land lay open and sunlit, grass bending beneath a wide sky.

There were no people, no buildings, no markers of time only space, light and quiet. It was not a place most would think to remember. On the back of the photograph were three words written slowly and deliberately inl’s steady hand. The ink had slightly bled with age, but the meaning was unmistakable.

Those words did not explain his life outright, but they answered a question his son had never fully known how to ask. Where I belonged.

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load