December 19th, 1944, a converted French army barracks in Verdd, France. The most powerful generals in the Allied command sat around a scarred wooden table, and not one of them was smiling. 3 days earlier, over 200,000 German soldiers had erupted through American lines in the Arden Forest like a tidal wave.

The offensive had caught Allied intelligence, completely flat-footed. American units were being overrun, surrounded, annihilated in the frozen forests. Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, had called this emergency meeting to figure out how to stop the bleeding. The situation was catastrophic.

The 101st Airborne was encircled at Baston. If that town fell, German armor could split the Allied armies in two and potentially reach the coast. Eisenhower looked around the table and asked the question that would define the next month of war. How soon can someone attack north to relieve Baston? The room went silent.

Generals stared at maps, calculating logistics, troop movement, supply lines, the distances involved, the winter conditions, the chaos of disengaging units already locked in combat. Dot. Then George Patton spoke. I can attack with two divisions in 48 hours. The other generals turned and stared at him. Some thought he was joking.

Others thought he was grandstanding, making impossible promises he could never keep. 48 hours to disengage three divisions from active combat. Rotate an entire army 90°. Move over 100,000 men and thousands of vehicles through snow and ice. and launch a coordinated attack against hardened German positions. Dot.

It was operationally impossible. Every general in that room knew it. But Patton wasn’t bluffing. He wasn’t grandstanding. He was the only general in that room who had seen this attack coming, and he had been preparing for it for 11 days. What the world didn’t know was that one man had predicted this disaster with chilling accuracy and the simple damning truth was that almost everyone had ignored him.

December 9th 1944 10 days before the Verdun meeting Patton’s headquarters in Nancy France Colonel Oscar Ko walked into Patton’s office carrying a stack of intelligence reports that would change the course of the war. Ko was Patton’s G2, his chief intelligence officer, meticulous, detailoriented, and deeply worried.

Doc Ko had been tracking German unit movements across the entire Western Front, and he had noticed something that nobody else seemed to care about. 15 German divisions had vanished. These weren’t small units. These were full strength divisions, including several Panzer divisions with hundreds of tanks. They had been pulled off the line and moved somewhere, but Allied Intelligence couldn’t find them.

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, SH AE, had an explanation. The Germans were holding these divisions in reserve to respond to Allied breakthroughs. Nothing to worry about, Ko didn’t buy it. He had been studying German patterns for months. The Vermacht didn’t hold 15 divisions in reserve just to react.

That was offensive strength. That was enough combat power to launch a major attack. Dot. Ko spread his maps across Patton’s desk. He pointed to the Arden Forest, the thinly held sector where American divisions were spread across miles of front. General, I believe the Germans are planning a major counter offensive.

The target is here, the Arden. Patton studied the maps while Ko laid out his case. The Arden was the weakest point in the Allied line. Four American divisions were holding a front that should have required 12. The terrain was difficult, heavily forested, narrow roads nearly impossible to navigate in winter.

That’s exactly why Schae wasn’t worried. The same terrain that made the Ardine hard to defend also made it hard to attack. No sane commander would launch a major offensive through that terrain in December. But Ko reminded Patton of something. In 1940, the Germans had done exactly that.

They had attacked through the Ardan and reached the English Channel in 6 weeks. It was the campaign that conquered France. Ko had more evidence. German radio traffic had increased dramatically in the sector. Prisoner interrogations mentioned new units arriving. Local civilians reported unusual activity behind German lines. Patton asked Ko a direct question.

If you’re right, when does the attack come? Ko’s answer was immediate. Within the next two weeks, Patton picked up the phone and called Omar Bradley, his immediate superior. He laid out Ko’s analysis. Bradley listened, but he wasn’t convinced. SHA intelligence disagreed. The war was almost over. Germany was beaten.

They didn’t have the strength for a major offensive. Bradley told Patton not to worry. Dot. Patton hung up the phone and looked at Ko. He didn’t say anything for a long moment. Then he gave Ko an order that would save thousands of American lives. Start planning. Over the next 10 days, Patton’s staff worked in absolute secrecy.

They developed three complete contingency plans for responding to a German offensive in the ADN nees dot. Each plan was detailed down to the minute. Truck routes calculated, fuel supplies prep-positioned, artillery batteries designated for rapid redeployment, infantry units assigned specific roads and assembly points.

The plans covered every variable. If the German attack came from this direction, Third Army would execute plan A if from another direction, plan B if the situation required a different response. Plan C. Patton’s staff thought their general had lost his mind. Third Army was engaged in offensive operations in the Sar region.

They were pushing toward Germany. Why were they planning for a defensive emergency 100 miles to the north? Because Patton trusted Oscar Ko more than he trusted Sha. On December 12th, Patton held a meeting with his senior commanders. He told them to be ready to disengage on short notice. He didn’t tell them why.

He just told them to be prepared. Dot. His commanders exchanged looks. Disengage from offensive operations. They were winning, but they were Patton’s men. They followed orders. Dot. By December 15th, Third Army was the only major American force with contingency plans for the Arden. Every other unit in the Allied line was focused on their own sectors.

Confident the war would be over by Christmas, 5:30 a.m. December 16th, 1944. German artillery erupted along an 80m front. Thousands of shells slammed into American positions. Then the infantry came. Then the tanks do three German armies. Over 200,000 men, smashing into four American divisions. The Americans were outnumbered nearly 4 to one.

Units that had been in quiet sectors for rest suddenly found themselves fighting for survival. Communication lines were cut. Commanders lost contact with their troops died at SH AEF headquarters. The first reports were dismissed as a local counterattack. It took hours for the scope of the disaster to become clear.

Dot at Bradley’s headquarters. There was only disbelief. This couldn’t be happening. Allied intelligence had assured them the Germans were finished. The 106th Infantry Division, newly arrived and positioned in the Arden for a quiet introduction to combat, was virtually destroyed. Two entire regiments surrendered.

The largest mass surrender of American troops in the European theater dot. But at third army headquarters, the reaction was different. Patton received the first reports and immediately summoned his staff. He looked at Oscar Ko. You were right. What’s their objective? Ko studied the incoming reports by Stone. They need the road junction.

And then Antworp. Patton nodded. Get me General Gaffy. We’re executing the contingency plans. While every other American headquarters scrambled to understand what was happening, Patton was already giving orders. Third army began disengaging from combat operations in the SAR. The other generals would spend three days trying to figure out how to respond.

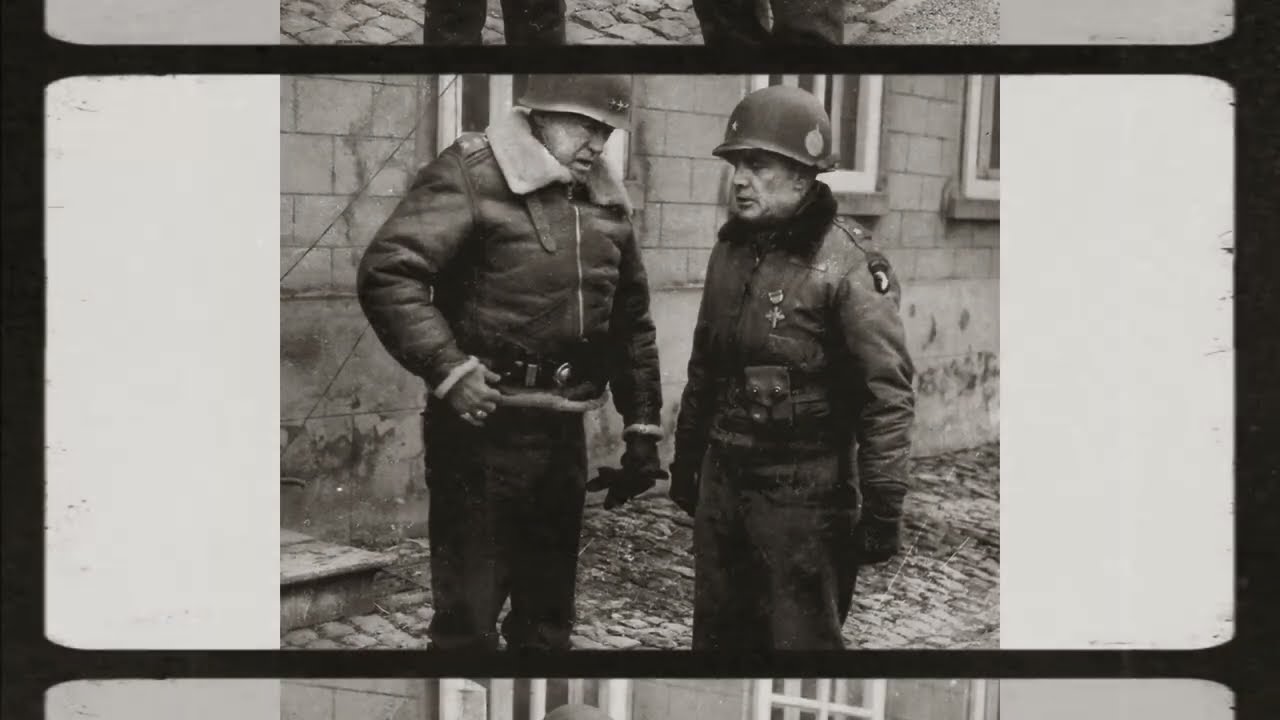

Patton had figured it out 11 days ago, December 19th, the emergency meeting at Verdun. Eisenhower had called every senior commander in the theater. The situation was grim, but Eisenhower opened with a statement that surprised everyone present. The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster.

There will be only cheerful faces at this conference table. Eisenhower understood something important. The German army had come out of its defensive positions. It was exposed. If the allies could respond quickly enough, they could turn disaster into victory. But responding quickly was the problem.

Every unit was in the wrong place. The logistics of turning everything around seemed impossible. That’s when Eisenhower asked his question. How soon can someone attack north to relieve Baston? The silence stretched. Generals looked at their maps. Calculated distances. Dot. Then Patton spoke. I can attack with two divisions in 48 hours.

Three divisions in 72. The room went quiet. Patton was known for aggressive promises, but this seemed beyond aggressive. This seemed delusional. Dot. Eisenhower pressed him. George, this is no time for grandstanding. The 101st Airborne is surrounded. If we promise relief and can’t deliver, those men die. Patton didn’t blink.

Ike, I’ve already given the orders. Third Army is disengaging now. I have three contingency plans prepared. I’ve been expecting this attack for 11 days. The other general stared. Expecting it? How could Patton have expected something that caught sh a ef completely by surprise? Eisenhower studied Patton for a long moment.

He had known Patton for decades. He knew when Patton was bluffing and when he was serious. Patton was serious. All right, George. Get moving. Patton left the Verdun meeting and made one phone call. He reached his chief of staff at Third Army headquarters. The message was brief. Play ball. Those two words activated contingency plans prepared 11 days earlier.

Within minutes, orders flowed through third army’s communication network. The fourth armored division began moving north. The 26th Infantry Division followed. The 80th Infantry Division prepared to disengage and redeploy. Truck convoys that had been prepositioned started loading troops. Artillery batteries began displacing to new positions.

Supply depots shifted from supporting offensive operations to supporting a relief attack toward Baston. 133,000 vehicles would move through snow, ice, and narrow roads. Supply lines running east were redirected north. units in combat that morning would be in combat again a 100 miles away within days.

The other allied armies watched in disbelief. They were still trying to figure out what was happening in the K anai in the Kung Arden third army was already responding. Dot every route had been planned every contingency considered every supply cash positioned. Patton wasn’t performing a miracle. He was executing a plan.

The movement began on the night of December 19th and continued without pause. Imagine turning an army, not a battalion, an entire army, over 100,000 men, thousands of tanks, trucks, artillery pieces, all moving simultaneously, all arriving at the right place at the right time. The weather was brutal. snow, ice, freezing temperatures, vehicles broke down, men suffered frostbite, but the movement continued.

Dot by December 21st, lead elements of the fourth armored division were in position. They had moved over a 100 miles in less than 48 hours through the worst winter, whether in decades while disengaging from combat operations. December 22nd, third army attacked. The fourth armored division drove north toward Baston. The fighting was brutal.

German forces had established defensive positions along every approach to the surrounded town. Every mile was contested. Tank battles erupted and frozen fields. Infantry fought through forests and villages. Inside Baston, the 101st Airborne held on. Low on ammunition, low on food, low on medical supplies.

On December 22nd, the Germans demanded their surrender. Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe sent back his famous one-word reply, “Nuts.” The paratroopers weren’t giving up. They knew relief was coming. December 26th, 1944. 450 p. M At first, Lieutenant Charles Boggas, commanding the lead tank Cobra King, pushed through the final German positions at a sane wall.

His tank made contact with elements of the 101st airborne. The siege was broken. Patton received the news and immediately called Eisenhower. We’re through to Baston. The relief corridor was narrow. German forces attacked the flanks continuously, but third army held. That night, supply convoys rolled into Baston.

Ammunition, food, medical supplies. The 101st Airborne had held for 8 days against overwhelming odds. Now they had what they needed to keep fighting. The Battle of the Bulge would continue for another month. The Germans hadn’t achieved their strategic objectives, but they had inflicted massive casualties. Over 19,000 Americans killed, over 47,000 wounded, another 23,000 captured or missing.

The bloodiest battle the American army fought in World War II, with the losses would have been far worse without Patton’s relief of Baston. If the 101st Airborne had been overrun, if the Germans had captured that road junction, the offensive might have succeeded in splitting the Allied armies.

The intelligence failure haunted American command. How had over 200,000 German troops achieved complete surprise? How had 15 divisions vanished without anyone noticing? The answer was simple and damning. Someone had noticed. Oscar Ko had tracked those divisions. He had predicted the offensive. He had identified the target.

But SH AEF had dismissed his analysis. The conventional wisdom said Germany was beaten. A major offensive was impossible. Only Patton had listened. Only Patton had prepared. And when the attack came, only Patton was ready. After the war, Allied intelligence officers interrogated captured German commanders about their planning for the Arden offensive.

The Germans had expected to reach the Muse River within 4 days. They had expected to take Antworp within 2 weeks. They had expected the American response to be slow, confused, disorganized. What they hadn’t expected was George S. Patton.German German commanders admitted that Patton’s counterattack disrupted their entire timetable.

The speed of third army’s response shocked them. They had calculated it would take the Americans at least a week to mount a serious counter offensive. It took Patton 4 days. General Gunther Blummetrret who served as chief of staff to Field Marshall von Runstet wrote in a post-war study that Patton was the most aggressive Panzer general of the allies.

General Hasso von Mant Tuffel who commanded fifth Panzer army in the Arden was more specific. We knew Patton would react quickly. We didn’t know he had prepared for our attack. When his counter offensive hit us, we realized someone on the American side had anticipated exactly what we were doing. That someone was Oscar Ko, but he was working for George Patton, and that made all the difference.

George Patton received no special medal for the relief of Baston. No unique recognition. The official histories praised Third Army’s performance, but rarely mentioned the 11 days of preparation that made it possible. Oscar Ko remained largely unknown outside military intelligence circles.

His prediction of the Ardan offensive, one of the most accurate intelligence assessments of the war, was overshadowed by the larger story of surprise and recovery. But within the military, the lesson was clear. Intelligence only matters if commanders act on it. Preparation only works if leaders trust their planners. SH h af’s intelligence failure wasn’t about incompetence.

It was about assumptions. The analysts had decided the war was almost over. They interpreted every piece of evidence through that assumption. Oscar Ko approached the evidence differently. He didn’t assume the war was winding down. He didn’t assume the enemy was broken. Instead, he asked a far more dangerous question.

What does the evidence actually show? What it showed was deeply uncomfortable. German units were moving at night. Radio silence was increasing. Divisions that should have been shattered were quietly reforming. Supply dumps were being rebuilt. Rail traffic was rising. None of it matched a prevailing belief that Germany was finished.

But having good intelligence wasn’t enough. Ko’s analysis was circulated through the chain of command. Bradley saw it. Shef reviewed it. Staff officers debated it. And then almost unanimously they dismissed it. They believed the Germans lacked fuel, manpower, and the ability to coordinate a major offensive. They believed the Arden was quiet because it was strategically irrelevant.

They believed what they wanted to believe. Patton didn’t. Patton trusted his intelligence officer, not because Ko told him what he wanted to hear, but because Ko showed his work. Patton read the reports, asked questions, and then did something few commanders were willing to do at that stage of the war. He prepared for a scenario.

Everyone else thought impossible. Dot at the Verdun meeting. When Patton said he could pivot his army north within 48 hours, the room went silent. Other generals stared at him in disbelief. Some thought he was exaggerating. Others thought he was performing as Patton often did. To them it sounded reckless. Even theatrical dot it wasn’t.

Patton wasn’t predicting the future. He was responding to evidence. He had already issued contingency orders. He had already studied the roads. He had already calculated the fuel requirements. He had already rehearsed the movement. 48 hours wasn’t bravado. It was math. When the German offensive erupted in the Arden, it exposed one of the greatest intelligence failures of the war. Warnings existed.

Signals were there. They were simply ignored at the highest levels. Assumptions replaced analysis. Confidence replaced caution. But it was also the story of one general who listened when almost no one else would. That is why Patton was the only senior Allied commander ready for the Battle of the Bulge.

Not because he was lucky, not because he was reckless, not because he guessed right. Dot because he prepared. And in war preparation is everything. If this deep dive into one of World War II’s most dramatic reversals fascinated you, then make sure you subscribe to this channel. We bring you the untold stories from history’s greatest conflicts, the hidden decisions that changed the course of wars and the overlooked figures who saw what others couldn’t or wouldn’t.

Hit the notification bell so you never miss the next episode. Because history’s most important moments aren’t always the ones you learned in school.

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load