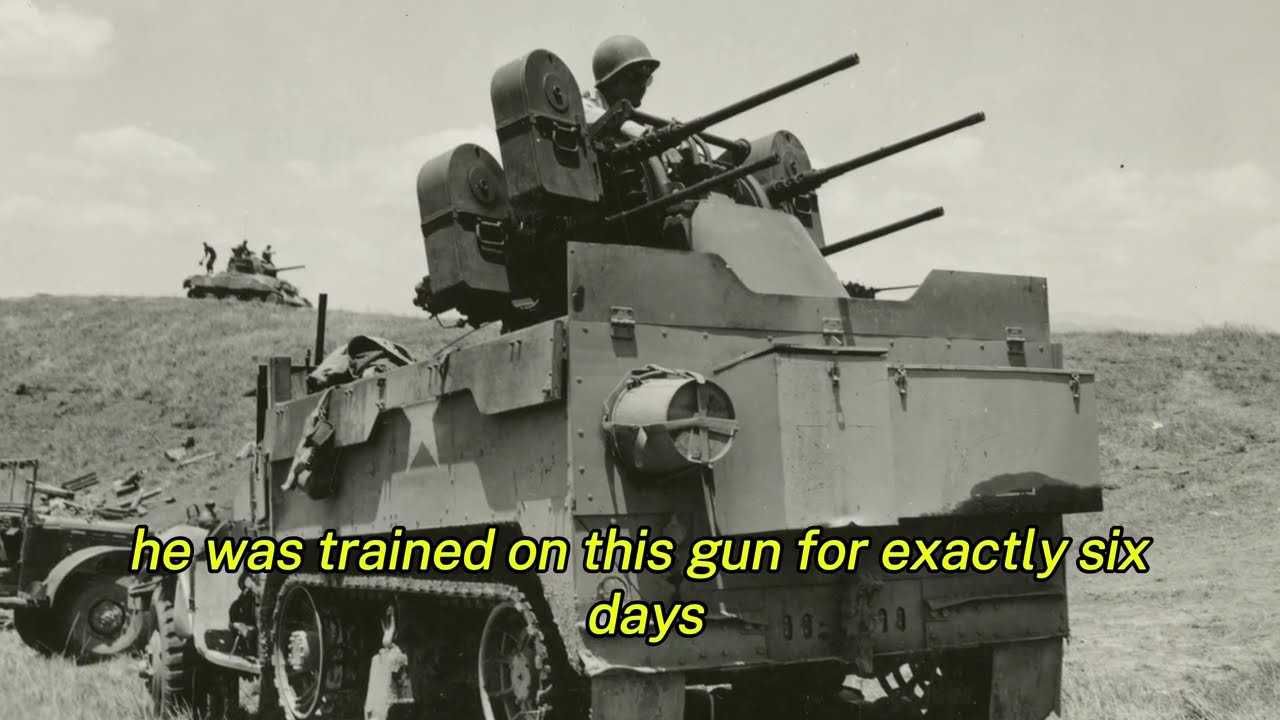

January 17th, 1945. Bastonia, Belgium. The temperature has dropped to minus15 Fahrenheit. Private James Edward Mitchell sits alone in frozen darkness so complete it feels solid. His numb fingers gripping the controls of an M51 quadmount anti-aircraft gun. A weapon that fires 2,000 rounds per minute and was never designed for what he’s about to do. Mitchell is 19 years old.

He was trained on this gun for exactly 6 days before being shipped overseas. He has never fired it in combat. His official job is to watch the sky for German aircraft. What he hears now is not coming from the sky. At 3:20 a.m., Private James Mitchell makes a decision that violates every principle of military doctrine he has learned.

He traverses the barrel of his anti-aircraft gun downward toward the ground. And without orders, without authorization, without any idea if he’s about to commit career suicide or perform an act of genius, he presses the firing pedal. Four 50 caliber Browning machine guns open fire simultaneously. 2,000 rounds per minute pour into the frozen darkness at nearly horizontal trajectory.

The effect is instantaneous and apocalyptic. Approximately 200 German soldiers from the second SS Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion had successfully infiltrated American lines. They were minutes away from signaling a main assault force. 1,500 soldiers supported by armor waiting in the forest to overrun the perimeter of Bastonia.

American centuries, exhausted from weeks of sub-zero combat, had missed them entirely. They wouldn’t miss what happened next. The 50 caliber rounds, each carrying 1,800 ft-lb of energy, hit human beings at 300 yd with consequences that were indescribable. The German assault force caught in the open with no cover was shredded in less than 15 seconds. Over 80 men died.

The rest fled. Mitchell held the trigger for approximately 15 seconds before his brain caught up with his actions. “Oh God,” he said aloud, his voice shaking. “Oh God, what did I do?” Sergeant Firstclass William Barnes exploded out of the nearby dugout. “What the hell are you shooting at?” Barnes screamed.

Mitchell, trembling, pointed at the ground. “The ground. In the years to come, official histories would sanitize this moment. They would call it initiative and quick thinking. They would award medals and cite it in training manuals. Decades later, military historians would credit this moment with fundamentally changing how the American military thinks about defensive weapons.

But the truth was simpler and stranger. A 19-year-old kid from Nebraska who had never fired anything larger than a hunting rifle had just made an accidental decision that would save approximately 2,000 American lives, disrupt a major German assault that nobody knew was coming and reshape anti-aircraft doctrine for the next 70 years.

The shocking part wasn’t that he did it. The shocking part was that nobody, not military planners, not senior commanders, not the Germans themselves, had ever considered that someone would. 3 months earlier, September 1944, Fort Bliss, Texas. James Edward Mitchell had enlisted on his 19th birthday, specifically to escape his father’s failing farm in Nebraska.

The youngest of four brothers, three of whom were already serving overseas, Mitchell had grown up hunting ducks and geese on the marshlands near Lincoln. He could track birds in flight. He could judge windage and distance instinctively. He could lead a target with the accuracy that came from years of reading the environment. Nobody knew yet how valuable those skills would become.

Fort Bliss in 1944 was processing thousands of replacements to replace catastrophic casualties from D-Day. The standard anti-aircraft training program, which had been 17 weeks before the war, was compressed to 8. 8 weeks to take civilians and turn them into gunners capable of engaging aircraft at supersonic speeds with weapons they’d never seen before.

The compressed timeline was catastrophic. The failure rate among trainees ran about 25%. Those who couldn’t master the technical aspects were reassigned to infantry or artillery, often a death sentence given the manpower crisis. Technical Sergeant Robert Hansen, the primary instructor, was a veteran of North Africa who had shot down three German aircraft over Tunisia.

On the first day of training, Hansen addressed the assembled recruits with characteristic bluntness. The life expectancy of an anti-aircraft crew under sustained air attack is approximately 45 minutes. That’s not 45 minutes of war. That’s 45 minutes once enemy aircraft starting your position specifically.

Your job is to shoot down anything with a swastika on it before it shoots you. You fire until your barrels melt, until you run out of ammunition, or until you’re dead. Simple as that. Nobody laughed. The problem was simple, but brutal. American anti-aircraft crews were being destroyed faster than they could be trained.

German Luftvafa fighters were still dangerous even in 1944. The V1 flying bombs, pilotless cruise missiles, were terrorizing England. Defending against that threat required crews who could acquire targets, calculate lead time, predict target movement, and execute firing solutions in seconds. Most of the recruits couldn’t do it.

They watched film of aircraft moving at 300 mph, and their brains simply froze. Leading a target requires spatial reasoning that exists in three dimensions simultaneously. The target is moving at enormous speed at unknown distance at unknown altitude. The gunner has to predict not where the target is, but where it will be in the next 5 seconds.

Get it wrong by even 30 feet and you’ve wasted ammunition and given away your position. Mitchell though something about his background translated perfectly. His hunting experience meant he already understood windage, distance judgment, and target prediction. When other recruits struggled, Mitchell was already thinking three steps ahead.

By week six of training, he was rated among the top five gunners in his company. instructors noted his exceptional target acquisition speed and recommended him for assignment to a veteran crew. On November 12th, 1944, Mitchell graduated. Within hours, he had orders for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, and immediate overseas deployment.

But here’s what the Army didn’t predict. that expertise at anti-aircraft gunnery and expertise at reading ground level movement in darkness are not the same skill set. The training Mitchell received was designed entirely around watching the sky. The field manuals, the doctrine, the procedures, all of it assumed a single purpose.

The doctrine was going to fail at Bastonia. When Mitchell arrived in Belgium in mid December, German forces had already begun their counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge. American positions were chaotic, exhausted, and running on fumes. Anti-aircraft crews like the one Mitchell joined weren’t just defending against air attacks.

They were defending a perimeter under siege. The expert consensus among senior commanders was clear. Hold the town. Don’t crack under pressure. Engage German aircraft when they appear. Maintain ammunition discipline. Nobody, not one senior officer, not one tactical planner, not one military strategist, anticipated what would actually happen in the frozen darkness on the morning of January 17th, 1945.

December 19th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. Battery B. 796th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion. Sergeant Firstclass William Barnes was a professional soldier. He had served since peaceime, fought in North Africa, survived Sicily and was approaching the status of combat legend. When he was assigned this new gunner, fresh from the States, Barnes didn’t waste breath on optimism.

“You’re the second assistant gunner I’ve had this week,” Barnes told Mitchell when they first met. The first one got hit by artillery two days ago. I’m not going to lie to you. This is bad. We’re surrounded. They’re throwing everything at us. You do your job. Stay alert. And maybe we both make it out of here. Mitchell’s first week at Bastonia was unlike anything his training had prepared him for.

The siege conditions were absolute. American forces were completely surrounded. Supply was dependent on rare air drops. The constant artillery bombardment created a psychological pressure that training exercises never replicated. The subzero temperatures meant frostbite was as dangerous as combat. Battery B’s four quad 50 mounts were positioned around Bastonia’s perimeter.

The official mission was air defense. But the reality was far more fluid. They engaged German fighters attacking supply planes. They provided ground support when infantry came under attack. They watched the sky during the day and the perimeter at night. On December 23rd, 1944, when the weather cleared enough for a massive resupply operation, Mitchell got his first taste of actual combat.

C47 transports dropped ammunition, medical supplies, and food. German fighters intercepted. Battery B engaged MI 109 fighters at 3,000 ft. Mitchell fed ammunition belts to Corporal David Walsh, watching the red tracers arc upward and seeing impossibly one of the German fighters trailing smoke. Did we hit him? Mitchell shouted over the gun’s roar.

Barnes watching through binoculars nodded. That’s a kill. Keep feeding those belts. The fighter spiraled down and crashed two miles outside Bastonia’s perimeter. Mitchell felt a surge of excitement mixed with nausea. He had just helped kill someone. The contradictory emotions would haunt him for days. By January 15th, 1945, Patton’s third army had broken through to Bastonia, but the fighting continued.

Germans launched repeated counterattacks. American forces exhausted and under strength struggled to hold their positions. On January 15th, Corporal Walsh was evacuated with severe frostbite in both feet. Barnes made a decision that would change everything. Mitchell Barnes said, “You’re primary gunner now.

You’ve got the best eyes in the battery. Torres, your assistant. We get a replacement loader tomorrow.” Mitchell spent the next day familiarizing himself with the primary gunner’s position. The Quad50s controls were simple in theory, complex in execution. Two hand grips controlled elevation and traverse. A foot pedal fired all four guns simultaneously.

A simple ring and post sight required the gunner to judge target speed, distance, and lead time instinctively. No computers, no radar assistance, just human judgment. and reflexes. The replacement loader arrived on January 16th. Private Eugene Patterson, 18 years old from rural Georgia, had completed training 3 weeks earlier and had been in Europe for only 5 days.

He made Mitchell look like a veteran. Barnes looked at his new crew, a 19-year-old primary gunner, a 21-year-old assistant, and an 18-year-old loader, and wondered what headquarters was thinking. We’re scraping the bottom of the barrel. Barnes told them that evening, “You boys are good kids, but you’re green.

Here’s how we survive. You follow my orders.” Exactly. You stay alert. You don’t panic. And you remember that this gun is the difference between our guys living and dying. Understood? They understood or thought they did. None of them predicted what would happen in less than 12 hours. January 16th, 1945.

Evening, Bastonia, Belgium. Gun position number three. The evening was quiet by Bastonia standards. Only sporadic artillery fire, no air attacks, no major ground action. Barnes established the guard rotation carefully. Mitchell, he ordered, you take 0200 to 0400 hours, the deadest part of the night.

That’s when exhaustion is greatest and vigilance is hardest to maintain. At Zoro 45 hours, Torres woke Mitchell from a restless sleep in the frozen dugout next to the gun position. Your turn. Nothing happening. Quiet night. Stay awake. Barnes will have your ass if you fall asleep on guard. Mitchell climbed out into darkness so complete it seemed solid. The temperature was -15 F.

His breath crystallized instantly. He could see perhaps 20 yard in starlight, barely enough to make out the silhouettes of trees at the forest edge. He settled into the gunner’s seat, hands on the controls, and tried to will himself alert. The doctrine for anti-aircraft guard duty was straightforward. Watch the sky.

Listen for aircraft engines. At the first sound of approaching planes, alert the crew and prepare to engage. Do not fire until Sergeant Barnes gave the order. Under no circumstances fire at ground targets or waste ammunition on unidentified contacts. Mitchell understood the doctrine. He had trained on it.

He knew the rules. But nobody had prepared him for the overwhelming crushing boredom of sitting alone in frozen darkness, staring at empty sky, fighting exhaustion, trying to stay alert when every instinct screamed for sleep. At 0315 hours, Mitchell heard something, not aircraft engines, something else. A faint mechanical sound, like metal on metal, coming from the direction of the forest. He strained to identify it.

Not artillery, not tanks, something smaller, closer. He rubbed his eyes, wondering if exhaustion was creating phantom sounds. Then he heard it again, definite now. The click of equipment, the muffled sound of movement. His training said aircraft. His instincts, honed by years of hunting in Nebraska forests, said something else entirely.

Something was moving in those trees. Multiple somethings moving carefully, trying to stay quiet, getting closer. Mitchell’s hands tightened on the gun grips. Standard procedure was to alert Barnes immediately. But what if he was wrong? What if it was just his imagination, exhaustion playing tricks? Barnes had been clear about not panicking, not raising false alarms.

The last thing Mitchell wanted was to wake everyone up over nothing. He stared into the darkness, trying to see what his ears were telling him was there. The sounds continued closer now. Definitely movement, definitely multiple sources. His hunter’s instincts were screaming that something was wrong, that predators were approaching, that danger was imminent.

Then at exactly 03 20 hours, he saw a movement, not in the sky. on the ground at the treeine approximately 300 yards away. Dark shapes low to the ground, moving with careful coordination, too many to count, too organized to be random, moving directly toward American positions. Mitchell’s mind, raced through possibilities.

Could be American patrols returning. Could be supply details. Could be nothing. But his instincts said otherwise. January 17th, 1945. Bastoni, gun position number three. Every rule Mitchell had learned told him the same thing. Wake Sergeant Barnes. Report the contact. Request permission to illuminate with flares.

Follow procedure. But the shapes were moving faster now, crossing the open ground between the forest and American positions. In seconds, they would be inside the perimeter. There was no time for procedure. Mitchell made a decision that violated every principle of anti-aircraft doctrine he had learned. He traversed the Quad 50 downward, aiming at the ground, he centered the site on the dark shapes moving across the snow, and without orders, without authorization, without any idea if what he was doing was catastrophically wrong, Private James Mitchell pressed the firing pedal. Four 50 caliber Browning machine guns opened fire simultaneously. 2,000 rounds per minute poured into the darkness at nearly horizontal trajectory. The tracers, one in every five rounds, created an impossible light

show as they stre across 300 yd at 2800 ft per second. The effect was immediate and apocalyptic. The dark shapes Mitchell had targeted were not American patrols. They were German infantry from the second SS Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion conducting a night infiltration attack. Over 200 soldiers moving in absolute silence intended to penetrate American lines cause chaos and signal the main assault force waiting in the forest.

The 50 caliber rounds designed to destroy aircraft traveling at supersonic speed hit human beings with devastation that training manuals never discussed. Each bullet carried 1,800 ft-lb of energy. At 300 yd, they barely slowed down. The German assault force caught in the open with no cover was shredded.

Mitchell held the trigger for approximately 15 seconds before his brain caught up with his actions. “Oh god,” he said aloud, his voice shaking. “Oh god, what did I do?” Sergeant Firstclass William Barnes exploded out of the dugout. Torres and Patterson right behind him. “What the hell are you shooting at?” Barnes screamed. “We’re under air attack.

” Mitchell, shaking violently, pointed at the ground. There, I saw they were coming at us. Barnes grabbed binoculars and stared into the darkness. The tracers had illuminated enough for him to see what Mitchell had fired at. His expression went from fury to shock to something like awe in the space of 3 seconds.

“Holy mother of God,” Barnes whispered. “You just killed how many?” “Torres,” he snapped. “Get on the radio now. Tell Battalion we have enemy infantry. battalion strength at least attempting to infiltrate our perimeter. Mitchell just stopped a godamn night assault. The radio crackled to life as Torres made the report.

Within minutes, American positions across the entire sector were on full alert. Flares went up, illuminating a scene of carnage that shocked even combat hardened veterans. Over 80 German soldiers lay dead or dying in the snow. The survivors had retreated to the forest, their infiltration plan completely destroyed. But Mitchell’s accidental engagement had revealed something far more significant than one failed attack.

The next morning, battalion headquarters, Colonel Marcus Hayes, Battalion Commander. You violated every rule of anti-aircraft employment, Colonel Hayes told Mitchell, his voice controlled but intense. You fired a strategic air defense weapon at ground targets without authorization. You wasted ammunition.

You compromised our anti-aircraft posture. Do you understand that? Yes, sir. Mitchell said quietly. Hayes paused. He studied the 19-year-old gunner, standing at attention, covered in gunpowder residue, eyes red from exhaustion. “You also detected an infiltration nobody else saw,” Hayes continued. “You reacted faster than trained centuries.

You disrupted a major German assault. You saved at least 2,000 American lives.” The room erupted in chaos. Officers were shouting at each other. Intelligence officers were demanding details. The regimental commander wanted to award a medal. Division staff was scrambling to understand how this had happened. Hayes raised his hand.

The room fell silent. Here’s what’s going to happen. Hayes announced. Officially, this never happened. We don’t need questions about why an anti-aircraft gun was firing at ground targets. Officially, alert centuries detected the infiltration and called for fire support. Unofficially. Hayes looked directly at Mitchell.

Unofficially? You just did something remarkable. Understood. Yes, sir. Mitchell replied. January 18th, 1945. Bastonia Battalion Headquarters interrogation room. The captured German officer was SS Sternbanfurer Klaus Hoffman, commander of the reconnaissance battalion that had attempted the infiltration.

During interrogation, Hoffman provided details that shocked American intelligence. “We had infiltrated successfully,” Hoffman stated, his German accent thick even in English. “Your centuries were asleep or inattentive. We were inside your perimeter preparing to signal the main assault.

Then suddenly one of your anti-aircraft weapons engaged us at ground level. The fire was devastating. We lost over 80 men in the first burst. The attack was compromised completely. Interrogators asked how the Germans had planned the assault. Hoffman explained that his battalion had been conducting reconnaissance of American positions for 5 days.

They had mapped sentry posts, identified weak points, and determined that American forces were exhausted and maintaining minimal night security. The plan depended entirely on surprise and speed. Once inside American lines, we would create chaos while the main assault force overwhelmed defenders who were confused and disorganized.

Hoffman said, “Your anti-aircraft gunner destroyed that plan. He paused, then added something that would reverberate through military doctrine for decades. We had accounted for centuries for patrol patterns, for listening posts. We never considered that someone would be watching the ground approach with an anti-aircraft weapon.

It was unexpected, impossible to plan for. January 19th, 1945, Fort Bliss, Texas. Anti-aircraft artillery training command. News of the incident spread like wildfire through the anti-aircraft community. By January 18th, every anti-aircraft crew in the division knew about the gunner who had fired at ground targets and stopped a German assault.

By January 20th, the story had reached third army headquarters. By the end of the month, it was being discussed in anti-aircraft artillery training programs back in the United States as an example of initiative and quick thinking. The statistics were stunning. German casualties. Over 80 killed in first burst, another 120 plus wounded or scattered.

American casualties prevented. Conservative estimates placed the direct casualty prevention at 2,000 PAL soldiers. Intelligence analysis suggested a breakthrough would have resulted in the annihilation of elements of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment. Tactical impact.

The disruption of the reconnaissance force prevented the signal for the main assault, which involved approximately 1,500 soldiers supported by armor, a force that would have overrun exhausted American positions in chaotic night fighting. Equipment validation. The Quad50’s effectiveness against masked ground targets at close range exceeded all previous calculations.

A single gunner had eliminated an entire German reconnaissance element that had evaded all conventional detection methods. February 1945, Fort Bliss, Texas, anti-aircraft artillery training school. Technical Sergeant Robert Hansen, Mitchell’s original instructor, was studying the afteraction reports when the incident first appeared in the training literature.

Look at this,” he told another instructor, pointing at the documentation. “A kid who’s been on the gun for less than a month on his first night of primary gunner duties detects and engages an enemy force that bypass trained centuries. And he does it by doing exactly what we told him never to do.” The implications were profound.

The anti-aircraft community had been operating under a doctrine that treated air defense and ground defense as mutually exclusive. But what if they weren’t? What if a weapon designed to engage fastmoving aerial targets could also serve dual purposes? The question rippled through the chain of command.

In March 1945, the anti-aircraft artillery command issued field circular number 1245, which officially recognized ground engagement as a legitimate employment of anti-aircraft weapons under certain circumstances. The circular cited lessons learned from European theater operations, particularly Belgian operations, though it didn’t mention Mitchell by name, but the implications were clear to anyone reading between the lines.

June 1945, Berlin, German War Department archives. Captured documents. American intelligence teams were examining captured German operational documents when they found the report from the assault that night. The Germans had even conducted their own afteraction analysis. The American anti-aircraft weapon employment at Bastonia represents a significant tactical innovation.

The German assessment stated enemy forces are apparently training anti-aircraft crews in dualpurpose roles utilizing surfaceto-air platforms for ground engagement in defensive positions. This capability was not previously anticipated. Operational planning for night infiltration assaults must now account for the possibility of horizontal fire from nominally air defense weapons.

It was an unintended compliment. The Germans were so convinced this was part of an official American doctrine change that they didn’t realize it had been an accident. The modern legacy. By the Korean War, anti-aircraft weapons were routinely employed in ground support roles. The same quad 50 mounts that Mitchell had used became standard defensive weapons for convoy protection and perimeter defense.

The M45 quadmount, successor to the M51, was specifically designed with ground engagement in mind, featuring lower elevation limits and improved sights for surface targets. The Vietnam War saw this evolution continue. Anti-aircraft weapons became primary defensive armament for fire bases and landing zones.

The principle that Mitchell had accidentally discovered that weapons designed for aerial targets could be devastating against ground forces became standard tactical doctrine. Today, anti-aircraft platforms are routinely deployed for dual purposes. Modern air defense systems are designed from the ground up with simultaneous ground and air engagement capability.

Tankbased air defense systems, towed platforms, self-propelled guns, all incorporate this principle of flexibility that traces back in part to January 17th, 1945 and a 19-year-old private who heard something in the darkness and reacted. If you’re amazed by stories of ordinary people making extraordinary decisions under impossible pressure, you need to subscribe to Last Words right now.

We’re uncovering the hidden histories that textbooks ignore, the true stories behind World War II’s most pivotal moments. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications so you don’t miss a single story. We upload new documentaries every week. February 1945, 796th Battalion transport to Rear Echelon.

After the incident on January 17th, battalion headquarters made a decision. Mitchell had combat experience now. He had proven himself under impossible conditions. He was more valuable as a trainer than as a line gunner. On February 23rd, 1945, Mitchell received orders transferring him stateside for instructor duty. The army had decided that his experience, particularly the Bastonia incident, made him valuable for training new anti-aircraft crews.

Sergeant Barnes pulled him aside the night before he left. “You know what you did, right?” Barnes asked. “You saved lives. Maybe my life.” Definitely a lot of other guys’ lives. You did good, Mitchell. I got lucky, Sergeant. Mitchell replied. I did everything wrong and it happened to work out. Barnes shook his head.

No, you did everything different and it worked out. There’s a difference. Sometimes doing things by the book gets people killed. Sometimes you need someone who doesn’t know the book well enough to be bound by it. Mitchell returned to the United States in March 1945 and was assigned to Fort Bliss as an anti-aircraft gunnery instructor.

He taught the same 8-week program he had gone through just 6 months earlier, but with additions based on his combat experience. He emphasized trusting instincts, maintaining awareness of ground approaches and understanding that anti-aircraft weapons could serve dual purposes. The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. Mitchell had been in actual combat for less than two months, but those two months had fundamentally changed him.

He was discharged from the army on November 3rd, 1945 with the rank of sergeant and a bronze star for his actions at Bastonia. The citation read, “For meritorious achievement in connection with military operations, Sergeant Mitchell displayed exceptional alertness and initiative while serving as anti-aircraft gunner during enemy action near Bastonia, Belgium.

His quick identification of enemy forces and immediate response prevented a successful enemy infiltration, saving numerous American lives. 1994 Washington D.C. 796th Battalion Reunion. 50 years after Bastonia, Mitchell attended his first battalion reunion. He had avoided these events for decades. Uncomfortable with the hero’s status, other veterans assigned him, but his wife convinced him to go.

At the reunion, he encountered a military historian researching anti-aircraft operations during the Battle of the Bulge. “Do you realize what you actually did?” the historian asked. “You didn’t just stop one attack. You fundamentally changed how the army thinks about anti-aircraft weapons.

Before Bastonia, they were single-purpose defensive assets. After Bastonia, they became flexible, multi-roll weapons. That change probably saved thousands of lives in Korea and Vietnam. I was scared, Mitchell said quietly. I heard something. I saw something. I did what seemed right at the moment. That’s all.

That’s always all it is, the historian replied. Nobody makes brilliant tactical decisions in combat. They make snap judgments based on limited information and hope it works out. The difference between disaster and success is usually just luck. You were lucky, but you were also alert, trained, and willing to act.

That combination is what matters. March 12th, 2006, Lincoln, Nebraska. James Edward Mitchell died at the age of 80. His obituary in the Lincoln Journal Star mentioned his service in the 796th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion and his Bronze Star, but provided few details about what he had done to earn it.

He had spent his post-war life quietly. He used the GI Bill to attend the University of Nebraska, studied forestry, and took a job with the Nebraska National Forest Service. He married Dorothy Hansen in 1950 and raised a family. He rarely spoke about the war. His wife knew he had served in an anti-aircraft unit.

His children knew he had been at Bastonia, but none of them knew the full story of what happened on January 17th, 1945 until that reunion historian documented it. The principle that remains, the Quad 50 mount that Mitchell used that night in January 1945 was probably scrapped after the war, melted down and recycled like most military equipment.

Nothing physical remains of the weapon that accidentally changed anti-aircraft doctrine and saved 2,000 lives. But the principle remains embedded in military training and tactical thinking. Anti-aircraft weapons can engage ground targets. Instinct matters as much as training. Sometimes the correct action is to violate procedure.

Sometimes the only way to succeed is to do something that makes no sense by conventional standards. These lessons, learned accidentally by a 19-year-old on his first night of combat duty, continue shaping how militaries think about defense, flexibility, and adaptation. Private James Mitchell didn’t revolutionize warfare.

He didn’t intend to change military doctrine. He didn’t plan to save 2,000 lives. He simply heard something moving in the darkness. He trusted his instincts. He did what felt right. Sometimes that’s all it takes to change history. Last Words brings you the stories that shaped our world.

The moments nobody expected to matter that ended up changing everything. From untold by heroics to forgotten military innovations. Subscribe now and join hundreds of thousands of history enthusiasts who are discovering the real stories behind the legends. Hit that subscribe button, turn on notifications, and let us know in the comments what’s the most incredible accidental discovery you’ve ever heard about.

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load