July 1945, Camp Livingston, Louisiana. The air hung thick with cypress mist and the slow hum of cicas. In a clearing near the messaul, Lieutenant Hiroshi Nakamura sat cross-legged beside a cast iron kettle suspended over crackling wood, watching catfish phyis turn golden in hissing oil.

Two years earlier, he had flown with the Imperial Navy, trained to believe that death for the emperor was the highest honor a man could achieve. Now he sat barefoot in enemy soil, surrounded by guards who smiled while watching their prisoners. The smell of frying fish twisted something deep in his chest.

Not disgust, but confusion so profound it felt like betrayal. When the old cinjun farmer handed him a plate, Nakamura raised a trembling fork to his lips, took one bite, and felt his entire understanding of war collapse. Before we continue, if you’re finding this story as powerful as we do, hit that like button and subscribe so you never miss these untold moments of history.

Drop a comment telling us where you’re watching from, whether it’s Tokyo, Louisiana, or halfway around the world. Your support keeps these forgotten stories alive. Now, back to that moment when a simple meal shattered everything Lieutenant Nakamura had been taught to believe.

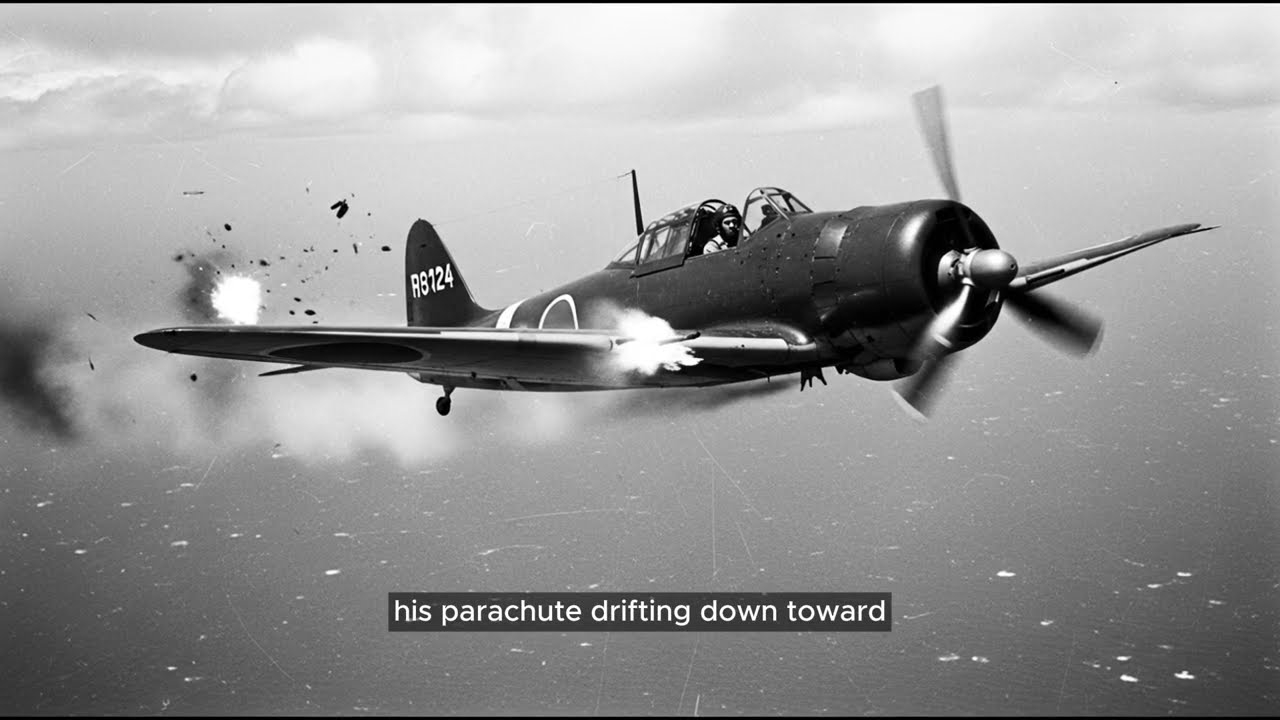

Because what happened next would prove that America had found a weapon more devastating than any bomb. The simple terrifying power of human decency. The journey to that Louisiana clearing had begun months earlier in the chaos of the Pacific War’s final year. Nakamura’s aircraft had been hit by anti-aircraft fire over enemy waters.

His parachute drifting down toward American ships like a white flag he never intended to raise. In the trainingmies at Yokosuka and Cure, instructors had drilled one truth into every pilot’s mind. Capture was worse than death. Surrender meant dishonor, erasure from family records, and torture at the hands of soulless Americans who would humiliate and destroy you.

Propaganda posters throughout Japan showed learing American soldiers with devil horns, trampling Japanese flags and laughing at prisoners. When enemy sailors pulled Nakamura from the Pacific, he closed his eyes and waited for the beating to begin. Instead, they wrapped him in a wool blanket.

They gave him water. One sailor, barely older than 20, offered him a cigarette with hands that didn’t shake with hatred, but with something Nakamura couldn’t identify, ordinary human nervousness. The confusion was so complete that Nakamura refused the cigarette, not from pride, but from sheer disorientation. Everything he’d been taught demanded cruelty. What he received was care.

The other prisoners whispered among themselves during the voyage to the mainland, their voices tight with fear. “They’ll starve us when we reach land,” one man muttered. “They’ll work us to death in mines,” another insisted. “They’ll extract our secrets and then execute us at dawn.” But when the ship docked in California, the barbed wire and punishment cells they expected never materialized.

Instead, there were medical tents staffed by American nurses who treated their wounds with the same antiseptic efficiency they would use on their own soldiers. There were showers with hot water. There were rations that included meat, bread, and coffee, luxuries most Japanese soldiers hadn’t tasted in years.

Nakamura kept waiting for the facade to crack, for the true American brutality to emerge. He maintained silence during interrogations, stone-faced and prepared for torture. But the questions were procedural, almost bored. The interrogators took notes, offered more water, and then sent the prisoners on their way. When Nakamura was loaded onto a train bound for Louisiana, he sat rigid in his seat, watching the American landscape roll past the windows.

The guards were relaxed, sharing chocolate bars and pointing out landmarks with the casual friendliness of tour guides. “Texas all be too hot for y’all,” one guard joked. “But Louisiana, that’s real food country.” The words made no sense to a man who’d been taught that enemies existed only to hate and be hated.

Camp Livingston emerged from the pine forests like something from a fever dream. It wasn’t a cage. It was a small city of wooden barracks, organized with the same meticulous efficiency that had crushed Japan’s war machine. A US sergeant gathered the new arrivals in the July heat and spoke in clear translated terms.

You’ll be treated fair here. You work, you eat, you rest. No one touches you. That’s the rule. To Nakamura, this sounded like an elaborate trap. How could an enemy speak of fairness? In the Japanese military, prisoners were livestock at best, beaten, starved, and worked until they dropped. Yet here stood an American sergeant promising protection to men who had killed his countrymen just months before.

That night, lying on a clean cot beneath a slowly turning ceiling fan, Nakamura stared into the Louisiana darkness and realized something that terrified him more than any torture could. He wasn’t afraid of dying anymore. He was afraid he’d been lied to his entire life. The sheets were soft.

The silence was profound. And somewhere in that silence, the foundations of everything he believed began to crack. By late summer, Camp Livingston had settled into a rhythm that felt more like farm life than imprisonment. The prisoners rose at dawn to the sound of a bugle, lined up for roll call, and ate breakfasts of oatmeal, bread, and coffee that would have been considered officers rations back home.

Then came work details, cutting timber, repairing fences, helping on nearby farms. The American guards didn’t bark orders. They gave instructions. Many were young men from Kansas, Alabama, and Louisiana. boys who treated their captives with distant politeness rather than cruelty. Some even learned basic Japanese phrases to communicate more clearly.

The strangest thing, the detail that kept Nakamura awake more than any other, was the equality of the meals. The same food served to the guards appeared on the prisoners tin plates. Fresh meat when available, vegetables, rice, occasionally even fruit. The camp operated under the Geneva Convention of 1929, which required humane treatment, equal rations, and medical care for all prisoners of war.

The United States followed those rules with bureaucratic precision. Some American soldiers grumbled that enemy prisoners ate better than civilians back home. But the orders came directly from Washington. We fight to preserve our values, not to betray them. One afternoon during fieldwork, Nakamura watched a young Japanese private collapse from heat exhaustion.

Before any prisoner could react, an American sergeant sprinted across the field, shouting for water and waving off other guards. Within minutes, a jeep from the camp infirmary arrived. The collapsed man was carried back, treated by American doctors, and returned to full health within days. That evening, sitting at the edge of his bunk, Nakamura stared at his tin cup and whispered to no one, “We treat our enemies like dogs.

They treat theirs like brothers.” The realization didn’t make him grateful. Not yet. It made him ashamed. Word of the incident spread through the camp like wildfire. The Americans had saved a man’s life instead of ending it. Something shifted in the prisoner’s collective consciousness. Men who had expected brutality found themselves responding to orders not from fear but from a strange uncomfortable sense of reciprocal respect.

What most of them didn’t understand was that the humane treatment was both moral and strategic. Washington believed that demonstrating fairness would undermine axis propaganda and establish moral high ground for the postwar world. It was working. Nakamura began to see that American strength wasn’t weakness disguised as mercy.

It was conviction, the belief that decency was inseparable from victory itself. The numbers haunted Nakamura more than any barbed wire ever could. Camp newspapers and bulletin boards posted facts with casual transparency. Over 425,000 Axis prisoners now held in the United States. Every P receives three than calories per day, exceeding Geneva standards.

Monthly cost per prisoner, 42 do or 150. To American administrators, these were simply logistics. To Nakamura, they were confessions of a strength Japan could never match. He remembered the stories filtering from home, civilians trading family heirlooms for rice, soldiers dying in jungle mud for lack of medicine.

Yet here in the enemy’s heartland, even captured men were fed meat, given medical care, and treated with procedural dignity. During one meal, Nakamura counted the plates at his table. 12 men, 12 portions, not one short. He glanced toward the kitchen where American cooks, black and white, worked side by side in the sweltering heat, laughing and cursing and passing each other, serving trays.

The chaos was loud, but it was alive. More alive than anything he’d seen in the rigid hierarchies of the Imperial military. That night, a radio in the messaul broadcast production figures. Tens of thousands of aircraft, millions of tons of steel, vast networks of rail and supply. Nakamura knew then that Japan’s war had been lost not on any battlefield, but in the factories and farms of a nation that could afford to feed even its enemies.

One evening, sweeping the barracks, he overheard two guards talking. “You know what’s crazy?” one said. “We spend more feeding these fellas than Germany spent feeding their whole damn army.” The other laughed. “Use that’s why we won, huh?” The words hit Nakamura like shrapnel. “They spent more feeding their prisoners than we spent saving our soldiers.

” That night he opened his journal and wrote in careful characters, “Our empire spoke of honor, of sacrifice, of death for the emperor.” But these men speak of efficiency, of fairness, of life. Which is the greater power? The question had no answer he could face. Days later, a truck arrived from a nearby town carrying donations from local civilians.

cornmeal, onions, fresh fish, even bottles of Coca-Cola. The guards joked that the Cinjun farmers had adopted the prisoners. Nakamura was stunned. He had believed kindness ended at the gun barrel. Here it extended beyond it, into kitchens and fields and small southern towns that had no strategic reason to care.

The camp newspaper published a figure that burned into his memory. America spends $1.8 8 billion annually to house its enemies humanely. To him, that wasn’t just a budget line. It was a moral equation. His people had spent everything on war and pride. The Americans spent billions on compassion and still had enough left over to win.

It was on a humid morning in late August that Nakamura’s understanding was tested in a way no statistic could prepare him for. He and a small work detail were sent beyond the wire to help a local cinjun farmer repair storm damage to his barn. The farmer, a stocky man named Tibido, with sunweathered hands and a slow Louisiana draw, looked at the prisoners, not with suspicion, but with something approaching sympathy.

“Y’all hungry?” he asked through the awkward translation of a guard. The PS hesitated. “Hungry?” Nakamura answered softly, unsure if it was a trick. Tibido nodded. Then we eat first. No man works on an empty stomach. He disappeared into his kitchen, and moments later, the smell hit them. Smoky, rich, impossible.

Crawfish simmering in a massive iron pot, corn and potatoes bubbling beside it, thick slices of sausage frying in bacon grease. to men raised on military rice and canned fish. The aroma was overwhelming. When a guard protested that prisoners weren’t supposed to eat with civilians, Tibido just waved a hand.

“You shoot me if it’s wrong,” he said. “But I ain’t feeding men through a fence.” His defiance silenced even the sergeant. They set up wooden tables beneath a pecan tree. The prisoners were seated first. Tibido dumped steaming crawfish onto paper covered boards, added corn, sausage, and thick slabs of bread. The PS didn’t move.

They thought it was a test that any moment someone would shout and drag the food away. But Thibido cracked a crawfish tail, grinned, and said, “Come on, boys. Food don’t bite.” One prisoner crossed himself. Another whispered in Japanese. Americans feed us like guests. Nakamura picked up a piece of sausage, hesitated as if it might explode, then took a bite.

The spice burned his tongue, but it wasn’t pain. It was sensation. Proof of life. He looked around and saw something he hadn’t seen since before the war. Men smiling. Even the American guards couldn’t help but join in, laughing as the prisoners fumbled with crawfish shells and winced at the cinjun spice. Someone brought out a harmonica.

Music drifted through the afternoon air, mingling with laughter and the clatter of shells hitting tin plates. For 2 hours there was no war. There were no victors or defeated, only men eating together under Louisiana sky. That night, back in the barracks, Nakamura couldn’t sleep.

He opened his journal and wrote a single line. They fed us without fear. They let us taste freedom and it burned hotter than war. Over the following weeks, the story of the Kinjun meal became legend inside Camp Livingston. Prisoners spoke of Tibido as if he were myth, an ordinary man who defied military orders to show kindness.

The camp command tried to discourage such fraternization, but the story spread faster than any regulation could contain it. To the Japanese officers, it was the ultimate confusion. In their empire, mercy was weakness. In America, it was law. When word reached Colonel Reeves, the camp commander, he didn’t punish anyone.

He simply said, “If feeding a man makes him remember his humanity, it’s worth more than a dozen guards with guns.” For Nakamura, the cinjun meal became the day he stopped being afraid. He’d been trained to see the enemy as demons. Now staring at the memory of crawfish and sausage, he realized the truth.

The Americans had already won, not because they were stronger, but because they refused to hate. The war ended in August with Japan’s surrender. But inside Camp Livingston, the conflict still echoed in the minds of men who’d spent months reconciling propaganda with reality. For the first time, the US government allowed Japanese PS to send censored mail home.

The letters were short, factual, and heavily inspected. But the truths that slipped past the red ink would carry more weight than any bomb. Nakamura sat on his bunk, pen trembling, trying to find words that could bridge two worlds. How could he explain this place to his wife Aiko, who still believed her husband was fighting for eternal glory? He began carefully.

My beloved Aiko, I am safe. The Americans are strange people. They smile too easily. They treat us fairly. They let us work and read. I do not understand it. I have eaten food richer than I’ve ever known. It is difficult to hate a people who feed you. He hesitated, staring at the half-finished page, then added quietly, “They are not devils, as we were told.

They are men, perhaps better men than we were.” When the sensor’s office reviewed the letter, Captain Donley read it twice, sighed, and approved it with a faint smile. “Let it through,” he said. “Truth’s a better weapon than ink.” Two weeks later, in wartorrn Nagasaki, Aiko received the letter.

She sat by a broken window, reading the page again and again. When she reached the line about kindness, she pressed it to her chest and wept. She wasn’t alone. All across Japan, similar letters arrived. Hundreds of them, each one a quiet rebellion against years of lies. Prisoners wrote about food, about decency, about guards who treated them as equals.

One officer wrote, “The Americans are powerful not because they hate, but because they don’t.” Another scribbled, “They feed us meat and call us sir.” Our empire taught us that respect was earned through fear. They earn it through fairness. Families copied the letters by hand, passing them from neighbor to neighbor, whispering that maybe the enemy wasn’t what the radio said.

By December, Japanese newspapers issued warnings against rumors of benevolent captivity. But it was too late. The truth had spread like smoke, impossible to contain. Inside Camp Livingston, Nakamura received a reply from Aiko. It was short and shaky from tears. You are safe. That is enough. But your words frighten me.

If kindness is stronger than honor, what have we fought for? He folded the letter and stared at it for a long time. Then he smiled faintly and said to himself, “We fought for something that no longer exists. Winter settled over Louisiana, and Camp Livingston felt less like a prison, more a threshold to the world beyond.

Repatriation news brought tentative hope. One morning, a beatup truck rolled in. Tibido, the cinjun farmer, appeared, offering jars of homemade peach preserves. Nakamura, stunned, shook his hand. The guards watched silently, recognizing a moment beyond military rules.

“If you feed a man, he can’t stay your enemy long,” Tibido said and left, leaving warmth in his wake. On departure day, prisoners lined up, given modest meals that now felt like abundance. Exchanges with the American sergeant revealed a fragile mutual respect. On the convoy to the port, Nakamura reflected in his journal.

Kindness had survived war where violence failed. Peaches accompanied them home, a symbol of mercy. Returning to Japan, he realized the true victory wasn’t conquest, but compassion. He became a teacher passing down the lesson that feeding an enemy can save both life and humanity.

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load