June 12th, 1945. Somewhere in Texas, the coals hissed beneath strips of pork. Smoke curled upward into endless blue sky. A young Japanese woman stood 30 ft from the grill, watching flames lick at meat, her hands knotted together. Every Sunday for 8 weeks, the same ritual. The guards offered. She refused.

They stopped asking why until one cowboy finally did. And when she answered, the laughter died, the music stopped, and every man there understood that some wounds can’t be seen, only tasted. Before you hear what she told them, hit that like button and drop a comment below telling us where you’re watching from.

Your support keeps these forgotten stories alive. The woman’s name was Satiko, 20 years old, a field medic with the Imperial Japanese Army. She had survived months of jungle warfare, starvation, and retreat. She had been captured in the Philippines, processed on a cargo ship, and transported across an ocean to a place she couldn’t pronounce.

And now she sat behind barbed wire in the heart of Texas, refusing to eat the one thing everyone else craved. Meat roasted over open fire. The cowboys thought it was pride. They were wrong. It was memory. Texas, 1945. The war was ending, but inside the wire, time moved differently. The camp held mostly German prisoners, a few Italians, and a handful of Japanese women, nurses, and auxiliaries captured in the Pacific.

Wooden barracks stretched in neat rows across flat earth. Dust coated everything. The heat pressed down like a hand. At its peak, Texas housed over 70 prisoner of war camps, more than any other state. more than 50,000 German soldiers alone. The guards were mostly locals, young men with drawing accents and sunscorched necks, cowboys in uniform. They weren’t cruel.

In fact, they were confusingly kind. They handed out extra bread when they thought no one was looking. They helped carry laundry buckets. They played harmonica on Sunday afternoons while pork ribs blistered on makeshift grills. The camp operated under Geneva Convention rules. Three meals a day, clean water, medical care, no beatings, no torture.

The prisoners worked, yes, picking cotton, repairing fences, but they were paid in script. At night, some of them played cards. It wasn’t freedom, but it wasn’t hell either. And that contradiction unsettled the Japanese women most of all. They had been taught that surrender meant death, that captivity was worse than a bullet, that Americans were savages who would humiliate and destroy them, but instead they were given soap, blankets, hot showers, and every Sunday barbecue.

The smell alone was enough to break some of them. Sachiko had learned medicine in a military hospital in Kyoto. She had been 19 when the orders came. Deployment to the Philippines. She remembered the ship, the way it rocked in blackwater seas. She remembered the jungle, thick as a wall, humming with mosquitoes and rot.

The men she served were skeletal, their eyes sunk deep. They had run out of quinine, then penicellin, then food. She stitched wounds with fishing line. She boiled leaves and called it tea. When the Americans closed in, the officers vanished in the night. They left the nurses behind. Alivven women in her unit.

By the time they surrendered, only five remained. One had walked into a river and didn’t come back. Another starved after refusing to eat wild roots, convinced they were poisoned. Sachiko had learned to chew slowly to trick her stomach into believing it was full. She had learned to ignore the screams that came from clearings in the jungle, the kind that started loud and ended in silence.

She had learned not to ask questions when the fire smelled like pork. But there were no pigs. The retreat had been chaos. No orders, no structure, just survival. They marched through villages already bled dry by occupation. Empty wells burned fields. The men grew feral with hunger. Discipline shattered. One night, Sachiko’s unit passed a clearing where smoke rose from a soldier’s fire.

The scent caught her before the sight did. Familiar, greasy, sweet, like roasted pork. But there hadn’t been pigs for months. She saw the fire. She saw the men chewing. She saw the bones. Then she heard the silence, the kind that settles not because peace has come, but because everything that made noise is gone.

A woman had been dragged from her hut the night before. A local, not military. Such had heard the screams. The next morning, she vomited in the bush. For days after, she couldn’t eat anything that had touched flame. The smell of charred meat became a trigger. A reminder, a ghost. Even now, months later, thousands of miles away, the scent of barbecue smoke turned her throat to stone.

She couldn’t tell the guards why. She didn’t have the words. Not in English, not in any language. How do you explain that the smell of Sunday dinner makes you remember murder? Every Sunday the ritual repeated. The guards wheeled out oil drums, packed them with hickory coals, and laid out slabs of pork, beef, and sausages.

The smoke rose like a signal. The other prisoners lined up eagerly. Germans laughed and joked. Even some of the Japanese women joined in, hesitant at first, but unable to resist. The meat was real. The portions were generous. Bread rolls, beans, coffee, Coca-Cola in tin cans. It was the first time in years any of them had eaten meat without ration tickets or sacrifice. But Sako sat apart.

Every week her plate was handed to her. Every week she accepted it politely, bowed softly, and set it down untouched. The bread, yes, the coffee sometimes, but the meat, never. At first the guards assumed it was cultural, maybe religious, maybe political, but she never explained. She never spoke much at all.

She worked diligently in the infirmary tent. She obeyed every rule. She bowed when addressed, but every Sunday the silence returned. Her eyes locked on the flames like they held a secret only she could understand. The other women whispered, “Some said she was proud. Others thought she was sick. A few called her stubborn, but no one asked until him. His name was Ellis.

He wasn’t loud like the other guards. He didn’t joke or flirt. He just watched. He moved carefully like someone raised by stillness. One afternoon, long after the coals had cooled, he found her mending a sleeve outside the infirmary. He crouched beside her and offered a tin of lemon candies from his pocket.

She took one out of politeness. They sat in the heat. Finally, he asked, not with curiosity, not with accusation, just concern. Why don’t you eat with the others? Sachiko stared at the dust for a long time. Then, in a voice so low it might have been mistaken for wind, she told him.

Not everything, not the names, but enough. She told him about the jungle, the hunger, the collapse, the fire, the smell, the silence. She didn’t use a word. She didn’t need to. Ellis understood. His face turned pale then still. He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t ask for more. He just sat with her while the sun crept lower and the wind stirred ash into the air.

She explained that no one had ever asked before. No one had ever looked at her and seen something worth understanding. Only ghosts had listened. Now someone real had. Bill had noticed her long before that day. He was older than most guards, a rancher before the draft. He had grown up on open land with horses instead of neighbors.

He carried himself like someone who knew how to mend fences with one hand, while calming a skittish colt with the other. His limp from a training accident made his walk distinctive, slow, uneven, but never hesitant. He wasn’t interested in politics or slogans. He cared more about weather than victory, more about whether cattle back home would survive winter than strategies printed in newspapers.

When Ellis told him what Sachiko had said, Bill didn’t speak for a long time. He just nodded. The next Sunday, something changed. The air smelled like dust and coffee, not smoke. The yard was quieter. The barbecue pit sat cold, untouched. No hickory, no fire, no meat. For the first time in months, there would be no barbecue.

It was a choice made quietly without announcements. The guards went about their duties with the same slow pace, but their hands were full of stew pots instead of brisket trays, bread, buttered, soup, hot and filling, coffee brewed in wide kettles. No grill, no ribs, no smoke. Bill didn’t look towards Sachiko when she stepped into the yard.

He just made sure the line moved smoothly, made sure she was served the softest bread, the hottest stew. The rest would be up to her. Sako hesitated at first. Her hands hovered over the tray as if expecting the weight of something darker. But when she looked down, there was no red meat, no charred edge, just soup, vegetables, beans, soft potatoes, and broth.

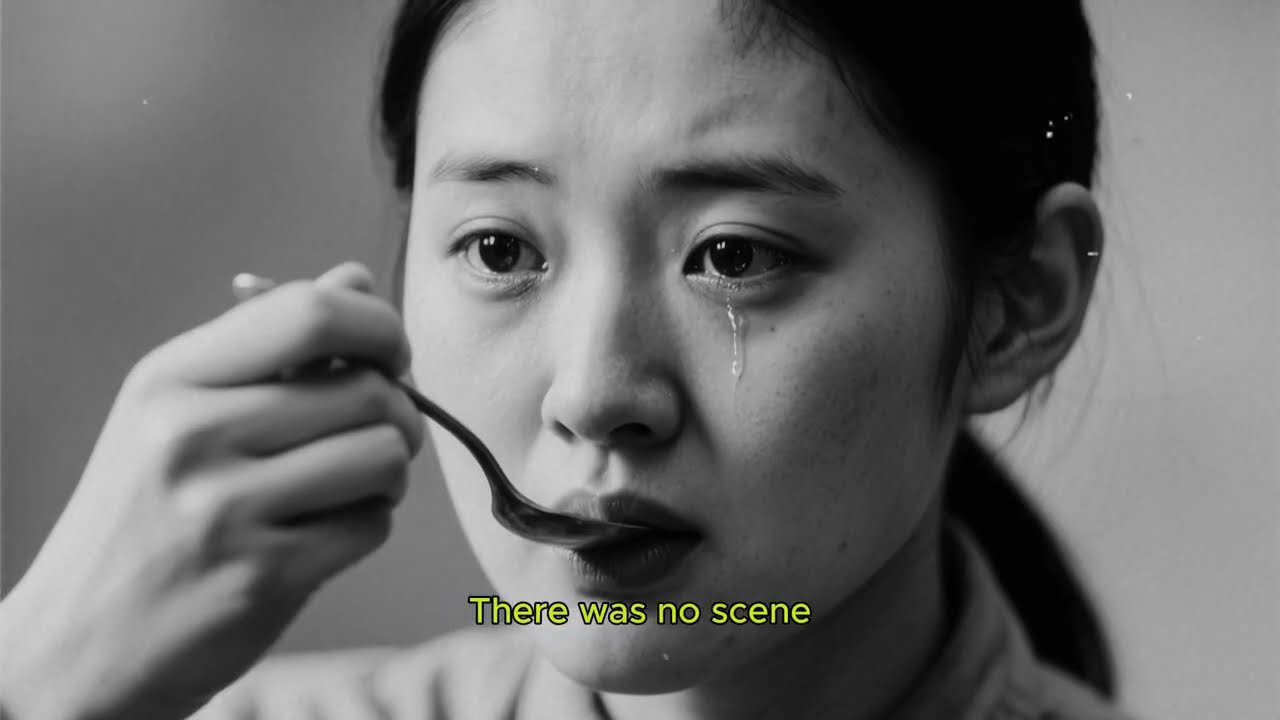

The kind of food a mother might serve a child after a fever. Her eyes lifted, scanning the camp, searching for the smoke trail that always signaled the day. It was not there. She sat, then slowly, as if her  muscles remembered how before her mind did, she ate. No one cheered. No one clapped.

muscles remembered how before her mind did, she ate. No one cheered. No one clapped.

A few women glanced, whispered, but nothing more. The guard said nothing. There was no scene, but the act itself, a quiet spoon lifted to trembling lips, was louder than any applause. She chewed slowly. The bread softened in her mouth. The stew filled her stomach like warmth after a long winter. For the first time in years, food did not carry the weight of memory.

It simply fed her. Across the yard, Bill caught her gaze. Not long, not heavy, just a brief nod. She returned it. Nothing more needed to be said. The paper was thin, nearly translucent, the pencil dull. But Siko wrote slowly, pressing lightly so the words wouldn’t tear through.

She hadn’t written home since the surrender. Not because she wasn’t allowed, but because she didn’t know what to say. What did one write from the belly of defeat? But after the stew, after the empty grill, the words came. She began with the phrase she always used when speaking to her mother. I am still here.

And then a line she didn’t expect to write. They stopped cooking the meat. That was all. No explanation. No drama. Just a sentence. Simple and quiet. But in that sentence lived a hundred unsaid things. Her mother, far away in a village carved by laws, would understand. The ritual of letter writing in the camp had begun as a surprise.

The Americans provided paper, pencils, envelopes. Once a month, letters could be sent home. Censored, yes, reviewed, but letters nonetheless. Satko had written only once before, a postcard barely three sentences. But now, with the smoke gone and the stew still warming her belly, she found herself wanting to speak.

She didn’t tell her mother about Belle. She didn’t mention Ellis. She didn’t describe the fire drawing or the long silence, but she didn’t have to. The sentence said enough. They stopped cooking the meat. Her mother would remember the stories Sajiko carried were not hers alone. Kindness rarely echoes loudly.

It moves in quiet pulses. In choices made without applause. The decision to cancel the barbecue wasn’t recorded in any military report. It wouldn’t be remembered in history books, but it was there in graphite on paper crossing the Pacific. A whisper that said, “She is healing.” Inside the camp, nothing visibly shifted.

There were still fences, still rules, still war, but something had softened. The fire had been put out, not just on the grill, but inside her. She folded the letter slowly, sealing it with trembling fingers. Far away in a home that smelled of rice and old wood, a mother would open an envelope, read a line, and cry.

Not from sorrow, but from something else, relief, hope, the knowledge that her daughter had not been destroyed by war. That someone somewhere had seen her pain and changed. That gesture, small as it was, rippled across an ocean. It said more than diplomacy ever could. It said, “You are human, and we see you.

” The notice came on a Monday, typed in English, translated clumsily into Japanese. Read aloud by a translator whose voice shook. The war was over. Japan had surrendered. The prisoners would be sent home. The women didn’t cheer. There was no celebration, no tears of joy, just silence. Some sat down where they stood.

Others clutched the fence with white knuckles. Freedom, they realized, was not a door flung open. It was a long, slow walk through unfamiliar light. Sachiko packed quietly. There wasn’t much to take. A folded blanket, thin but clean. A small diary, pages filled with single lines, scattered memories, and the flower pressed between two pages of the camp issued Bible she had never opened.

It lay flat and brittle. Its purple faded to ash gray. She carried it like a relic, not of faith, but of change. The journey back was slow. Trucks to trains, trains to ships. Then the ocean, vast, endless, gray, like memory. She stood at the rail for hours, watching smoke from the ship curl into the sky.

It reminded her of the grill, of Bill’s silence, of Sundays without fire. When she left, there were no goodbyes, no ceremony. But as she boarded, she saw Bill one last time, standing beneath the awning of the barracks. He didn’t wave. He just touched the brim of his hat, then lowered his hand and turned back toward the yard. That was enough.

Japan was rubble. Streets bombed flat. Families scattered. Cities cracked open like eggshells. But it wasn’t the ruins that shook her. It was the faces. The way people looked at returnees with quiet calculation. Were you captured? Did you surrender? Did you shame us? S Chico kept her head down. She said little.

She returned to the village alone. Her mother, thinner now, older by decades, wept without sound when she saw her. They didn’t speak of the war that night. They didn’t need to. Later, Sachiko showed her the diary, opened the page with the flattened flower. Her mother touched it gently, then touched her daughter’s hands.

hands that had once trembled at the scent of pork fat. Now they were steady. She didn’t speak of the grill. She didn’t tell the villagers about stew or coffee or the man with the limp. What she carried was not a tale of mercy or forgiveness. It was something quieter, a memory of dignity returned in small gestures, a nod, a change in menu, a moment of being seen.

Her commanders had prepared her for pain, for starvation, for death, but they had not prepared her for kindness, for the way it lingered, for the way it unraveled everything she thought she knew about enemies and honor. In time she planted flowers behind the house, the same kind, soft purple blooms that swayed in the wind.

When they blossomed, she would press them into books and to letters, and to places only she would look. Her children would one day find them and ask why. She would tell them only this, that someone once chose not to light a fire, and in that small refusal, in that quiet mercy, she found a way to breathe again. Not all survivals are loud.

Some arrive softly, like a hand easing off a match, like a moment allowed to pass without violence. It was enough. It carried her forward when memory threatened to pull her under. The grill in Texas was dismantled after the war. The camp closed. The barracks were torn down plank by plank, their shadows erased. The land was returned to ranchers and cotton fields.

The soil pressed flat again as if history itself could be smoothed away. Winged moved through the grass where fences once stood. Cattle grazed where guards once watched. Time did what it always does and moved on. But somewhere in a village in Japan, a pressed flower remained, tucked between pages, delicate and unchanged.

It held the shape of a day when cruelty paused. A small proof that even in a world organized around destruction, restraint could still exist. War is fought with bullets and bombs. Everyone knows that its noise is impossible to miss. But healing begins with something smaller. A bowl of stew offered without words.

A nod across a yard where suspicion once lived. A fire that was never lit. Not every act of courage happens on a battlefield. Sometimes it happens at a barbecue pit on an ordinary Sunday when someone chooses to see past the wire, past the uniform, past the enemy, and recognizes the human underneath.

Courage does not always announce itself with gunfire or metals. Sometimes it is quiet, almost invisible, found in restraint rather than action, and what is refused rather than what is done. That Sunday in Texas, no smoke rose into the sky. No flames leapt. The air remained still, untouched by fire or fury.

The moment passed without spectacle, unnoticed by history, unmarked by record. Yet within that silence, something shifted. A boundary softened. A life moved forward instead of breaking. In a war defined by destruction, understanding rose where violence might have been. It did not roar or demand attention. It simply existed, fragile and rare.

And in a world torn apart by war, that understanding born in an ordinary place on an ordinary day was the rarest thing of

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load