August 31st, 1943. Rabul, New Britain. The operations tent smelled of sweat, engine oil, and volcanic ash. Lieutenant Commander Saburo Sakai stood beneath a canvas roof that did little against the oppressive heat, holding a piece of intelligence paper in his weathered hands. One eye was a milky void, a gift from an American tail gunner over Guadal Canal.

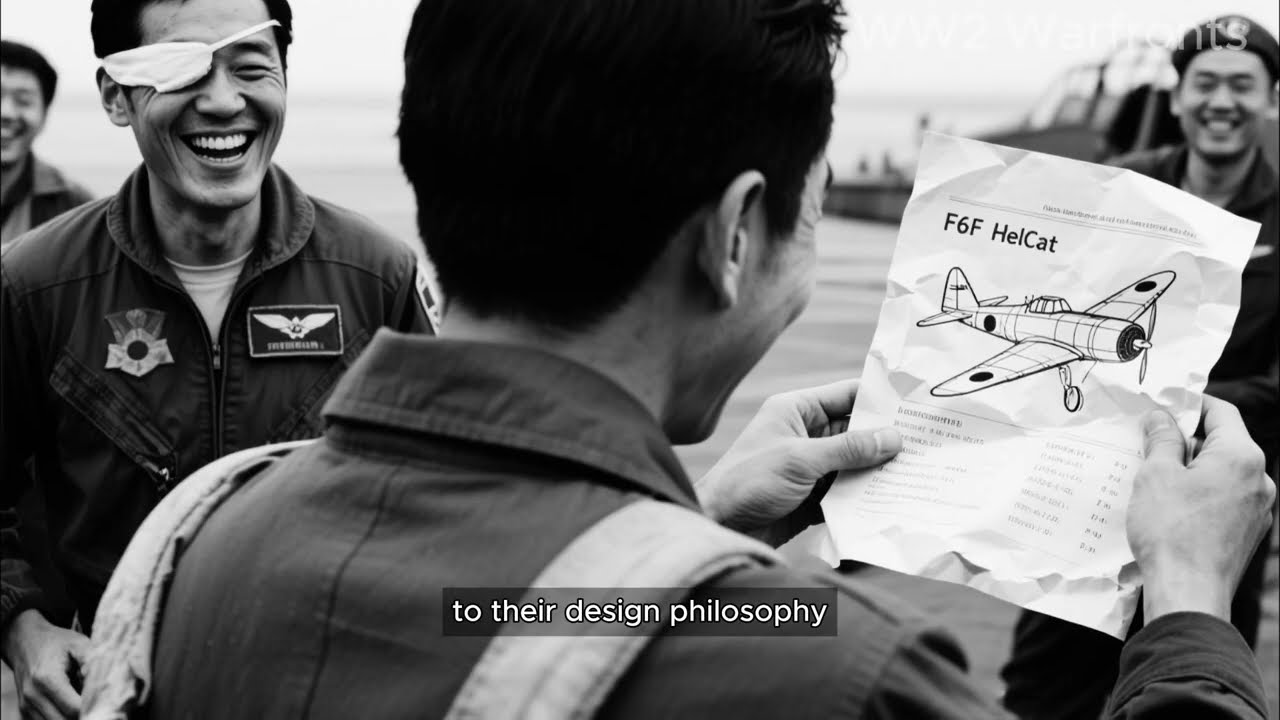

But his good eye, the eye that had guided him through 64 confirmed kills, scanned the report with methodical precision. Then he laughed, not a polite chuckle, a genuine, dismissive laugh that echoed across the humid afternoon. Around him, the elite pilots of the Tynan air group joined in. They were reading about America’s new fighter, the F-6F Hellcat.

The specifications were absurd. loaded weight nearly 13,000 lbs, more than twice their beloved zero. Wing loading so heavy it suggested a turning radius approaching a,000 ft. The Zero could turn inside 600. It carried over 200 lb of armor plate. Armor. The word itself was foreign to their design philosophy.

The Americans were sending a truck to fight a sword. They were building machines while Japan cultivated warriors. Sakai looked through the tent opening at the row of zeros gleaming on the pierced steel planking. Those aircraft had swept the skies of every opponent thrown against them for two solid years. British hurricanes, American P40s, Dutch Brewster Buffaloos, all had fallen before the Zero’s impossible agility and its pilots supreme skill.

This new American plane was just another target. heavier, clumsier, slower to turn. It would die like all the others. But as Sakai folded the report and tucked it into his flight suit, he could not have known that the laughter in that tent was the last sound of an ending world. The Hellcat was not coming to duel.

It was coming to exterminate. In less than 24 months, this joke of an aircraft would claim over 5,000 Japanese planes, achieve a kill ratio of 19 to1, and systematically destroy Japanese naval aviation so completely that the very idea of air combat would be transformed forever. The samurai of the sky were about to meet industrial warfare, and they would learn too late that you cannot turn inside a system that refuses to turn at all.

Before you continue this story, we want to ask, where are you watching from today? From Tokyo, Texas, or Tanzania. It’s incredible that people from every corner of the globe gather here to remember these moments that shaped our world. If you’re new here, hit that subscribe button and join this community that refuses to let history fade.

Now, back to 1943, where the myth of invincibility was about to shatter. To understand why the Japanese pilots laughed, you must first understand the legend they were defending. The Mitsubishi A6M0 was not just an aircraft. It was proof of a philosophy. When Jiro Horicoshi sat down to design it in 1937, the Imperial Japanese Navy gave him an impossible task.

Build a carrier-based fighter faster than any land-based fighter in existence. Give it twice the range. make it more maneuverable than anything in the sky. Horicoshi achieved the impossible by making a deal with physics itself. He sacrificed everything for performance. The Zero was constructed from a top secret aluminum alloy called extra super duralamin.

Strong as steel, light as dreams. Its empty weight was 3,700 lb. Its wing loading just 22 lb per square foot. These numbers translated into something mystical in the air, a turning radius that defied belief, a climb rate that seemed supernatural. But the price for this performance was paid in blood. There was no armor around the pilot.

A single bullet in the right place meant death. There were no self-sealing fuel tanks. One tracer round could turn the entire aircraft into a fireball. The radio was often removed to save weight. Every ounce that did not contribute to speed, range, or agility was discarded. The philosophy was pure.

The warrior’s skill was paramount. The machine was merely an extension of his will. Victory belonged to the superior spirit guided by superior training. And for 2 years, the philosophy worked perfectly. At Pearl Harbor, Japan lost 29 aircraft while destroying over 300 American planes. In the Philippines, seven Japanese fighters down against 103 American aircraft destroyed.

The numbers were so one-sided they seemed like propaganda. When American engineers finally captured an intact zero on Autan Island in 1942, they refused to believe the performance data. A fighter with a bombers’s range, a biplane’s agility, and guns that could shred anything it faced. They tested it repeatedly.

The numbers held. The Zero could outturn, outclimb, and outrange every fighter America fielded. It was a masterpiece, but it was a masterpiece designed for 1941, and the Americans were designing for 1945. When the first intelligence reports on the Grumman F6F Hellcat reached Japanese headquarters in early 1943, they confirmed every prejudice held by the Imperial Naval Air Service.

The Americans had learned nothing. They were still building heavy, clumsy machines that tried to substitute metal for skill. The specifications read like a catalog of design failures. Loaded weight 12,752 lb. The zero and combat weight barely touched 5800. Its wing loading was 36 1/2 lb per square foot.

In a turning fight, this meant the Hellcat would be a lumbering giant trying to catch a dragonfly. It carried six 50 caliber machine guns with 2400 rounds of ammunition. The weight of the guns alone exceeded what some fighters weighed empty. It had bulletproof glass, self-sealing fuel tanks, a massive Pratt and Whitney R2800 double Wasp engine producing 2,000 horsepower.

The Americans were building a fortress with wings. To Japanese tacticians, this was evidence of American weakness. Their pilots lacked the skill to survive without armor. Their training was insufficient, requiring heavier firepower to compensate. Their industrial capacity was being wasted on adding weight that would make the Hellcat easy prey in the turning dog fights that defined air combat.

Captain Minoru Jenda, the tactical genius who planned Pearl Harbor, wrote a dismissive analysis that circulated through Japanese command. The specifications, he concluded, represented the continuation of a failed philosophy. The Americans were attempting to overcome pilot skill with machinery. A zero would fly circles around it.

The mathematics seemed irrefutable. Japanese doctrine was built entirely around the horizontal turning fight. Get into a turning circle with your opponent. Use your superior agility to slide onto his tail. Finish him with a burst from your 20 mm cannons. Based on pure numbers, the Hellcat was designed to lose this fight every single time.

The Japanese saw what they expected to see, a heavy armored truck trying to compete with a precision instrument. They did not see what the Americans had actually built. The Americans had studied the Zero strengths and built an aircraft specifically designed to make those strengths irrelevant. They had examined Japanese tactics and created a system that refused to engage on Japanese terms.

The Hellcat was not meant to turn with the Zero. It was meant to hunt it using a completely different grammar of warfare. September 30th, 1943, near Marcus Island. Petty Officer First Class Yoshio Fukqui was escorting a reconnaissance plane when he spotted six dark shapes climbing from the southeast. His first thought, recorded in his afteraction report, was that they were B25 bombers.

They were too large, too bulky to be fighters. Then the shapes banked and Fukui saw the silhouette clearly. A massive radial engine, a thick barrel-chested fuselage, wings that looked almost stubbornly short for such a heavy body. His brain processed the information. This must be the new American fighter, the one they had laughed about. The flying truck.

Fukulei felt no fear, only professional curiosity. He rolled his zero into a diving turn, the standard opening gambit. He would use his aircraft’s legendary agility to slice inside the American’s turn, get on his tail, and end this quickly. He expected the heavy Hellcat to lumber forward, unable to follow his maneuver.

Instead, the Hellcat did something that violated every principle of air combat as Fukui understood it. It went vertical. The American simply pointed his nose at the sky and climbed. Not slowly, not laboriously. With a raw, terrifying power Fukui had never witnessed. The Pratt and Whitney R2800 double Wasp, all 18 cylinders and 2,000 horses of it, pulled the six-tonon Hellcat upward at 3,500 ft per minute.

Fukulei tried to follow. His Zero, designed for horizontal agility, shuddered as its less powerful Nakajima engine fought gravity. His airspeed bled away. At 15,000 ft, the Hellcat performed a perfect hammerhead stall turn and dropped onto Fukui’s tail like a falling anvil. The American opened fire. Six guns, not four.

The volume of fire was apocalyptic. 17 50 caliber rounds per second tore through Fukui’s unarmored fuselage. Only by throwing his aircraft into a desperate spin did he escape. He limped back to Marcus Island, his plane riddled with holes. His wingman never returned. Neither did the reconnaissance plane they were protecting.

The first blood had been drawn. The joke had just killed two Japanese aircraft without breaking a sweat. And this was only the beginning. October 5th, 1943. Wake Island. Lieutenant Yoshio led 12 Zeros to intercept another American carrier raid. They climbed to 20,000 ft, achieving perfect position. Altitude, surprise, tactical advantage.

Everything was in their favor. Below them, 12 Hellcats flew in loose formation. This would be textbook, a classic bounce from above. The Zeros dove. But as they screamed down on the American formation, the Hellcats did something baffling. They did not panic. They did not scatter. They did not attempt to turn and engage.

They simply nosed down slightly and accelerated. The Zeros, built for agility rather than speed in a dive, could not catch them. Japanese pilots fired for maximum range, watching their bullets spark harmlessly off armored fuselages. They were hitting planes with 212 lb of armor plate protecting the pilot. Planes with self-sealing fuel tanks that could absorb dozens of hits.

The Zero, which could be brought down by a handful of well-placed rounds, was firing at a flying tank. Then the Hellcats executed their counterattack, not with turning, with physics. They used their massive engines and their weight as weapons. They climbed. They used their superior horsepower to regain altitude faster than the Zeros could match.

At high altitudes, the Zeros non-supcharged engine gasped for air. At 25,000 ft, the Hellcat was still a beast. The Americans came down in slashing high-speed passes. What they called boom and zoom tactics. Dive. Fire those six terrible guns. Climb away before the zero could react. It was clinical, efficient, devastating.

Eight zeros were shot down in minutes. Not a single Hellcat was lost. Lieutenant Shiga wrote in his diary that night that the Americans had changed the rules. They no longer fought like warriors. They fought like executioners. The horrifying truth was spreading across the Pacific.

The Hellcat was not designed to outturn the Zero. It was designed to make turning irrelevant. The Americans had developed something the Japanese could not comprehend. A system. Lieutenant Commander John Thatch had created a tactic called the Thatche, where two fighters flew in intersecting patterns that covered each other perfectly.

If a zero pursued one Hellcat, the other was already in position to kill it. The Japanese trained as individual samurai were facing coordinated machinery. But the technology gap went deeper. American carriers were equipped with radar that could detect incoming Japanese formations from 70, 80, even 100 miles away.

Fighter directors sat in darkened rooms staring at glowing screens, positioning Hellcats with chess master precision. While Japanese pilots scanned the vast sky with naked eyes, relying on luck and instinct, Hellcat pilots were being guided to perfect intercept positions. They arrived with altitude advantage with the sun at their backs from the enemy’s blind spots.

The Japanese were blind men fighting opponents who could see in the dark. and the technology extended to the planes themselves. The Hellcats six Browning M2 50 caliber machine guns fired a combined 4500 rounds per minute. Each bullet carried four times the kinetic energy of the Zero’s smaller rounds.

A 1second burst put a devastating stream of lead into the air, enough to shred the Zero’s delicate unarmored frame into confetti. But perhaps the most decisive factor was not the planes or the tactics or the radar. It was the pilots. Japan had begun the war with a small elite cadre of supremely trained aviators.

Their training program required 3 years and 700 flight hours before a pilot saw combat. They were the best of the best, but they were a finite resource and America was killing them faster than they could be replaced. By 1944, the attrition was catastrophic. The three-year program was a memory. New Japanese pilots were being rushed to the front with 200 flight hours, then 100.

Fuel shortages meant training was done in gliders or obsolete aircraft. Gunnery practice was limited to a handful of rounds. They were being sent to fight the deadliest fighter system ever created with barely enough training to safely take off. Meanwhile, American pilots arrived in the Pacific with 500 hours of flight time, 50 of those in the Hellcat itself.

They had fired thousands of practice rounds. They had practiced carrier landings until it was muscle memory. They had learned boom and zoom tactics over Texas, not in Mortal Kombat against veteran aces. The samurai were all dead. Japan was sending children to fight professionals. June 19th, 1944. The Philippine Sea.

Japan committed its entire remaining carrier force to one final decisive battle. Nine carriers, 450 aircraft, everything they had left. Against them sailed Task Force 58, 15 American carriers, 950 aircraft, 450 of them F6F Hellcats. Admiral Jizaburo Ozawa launched his attack in four waves, still believing that the spirit of his pilots and the range of his aircraft would bring victory.

The first wave of 69 Japanese aircraft was detected by American radar when they were still 150 mi away. Fighter directors calmly vetored dozens of Hellcats to perfect interception points. They set up the ambush with precision. Massive altitude advantage, sun at their backs, approaching from the Japanese formation’s blind spots.

When the first wave of Japanese planes arrived, they flew into a steel curtain. An enormous wall of dark blue Hellcats stacked in layers from 20,000 to 30,000 ft. Waiting. The engagement lasted 12 minutes. 42 of the 69 Japanese aircraft were shot down. The Zeros tried to engage in turning dog fights. The Hellcat pilots simply refused.

They made high-side runs, shot planes down, and zoom climbed back to altitude. When Zeros tried to follow, they stalled, and another Hellcat picked them off. Wave after wave flew into the buzzsaw all day long. By sunset, Japan had lost 346 carrier aircraft. American losses totaled 30 aircraft from all causes.

In the ready rooms that night, American pilots joked that it was just like an oldtime turkey shoot back home. The name stuck, the great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot. The Imperial Japanese Navy’s carrier air arm, the force that had terrorized the Pacific for two and a half years, effectively ceased to exist in a single afternoon.

The psychological impact on the few surviving Japanese pilots was profound. They were no longer fighting men. They were fighting an invisible, allseeing system that guided an indestructible monster. Admiral Ozawa wrote in his report that the Americans had achieved something thought impossible. the industrialization of air combat.

Unable to compete conventionally, Japan resorted to the kamicazi. Vice Admiral Takajiro Onishi justified it with brutal logic. If a zero attacks conventionally, the probability of success is near zero. The Hellcats will destroy it. If the zero becomes a bomb, the probability of hitting increases to 30%. The pilot dies either way.

At least as a kamicazi, his death has meaning. It was the final admission of the Hellcat’s total dominance. The only way to penetrate the system was to turn pilots into guided missiles. Even here, the Hellcat proved its worth. During the battle for Okinawa in 1945, Japan launched nearly 2,000 kamicazi sordies. Hellcats flew tens of thousands of combat air patrols, forming a protective umbrella over the fleet.

They shot down an estimated 80% of the suicide attackers before they reached their targets. When the war ended, the scale of American industrial might became clear. The Grumman factory in Beth Page, New York, had operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. At peak production in 1944, a brand new F6F Hellcat rolled off the assembly line every single hour.

Grumman built 12,275 Hellcats in just 30 months. In 1944 alone, America produced 35,000 fighter aircraft of all types. Japan that same year managed just over 5,000. Jiro Horoshi, designer of the Zero, studied a captured Hellcat after the war. His conclusion was devastatingly simple. We designed an aircraft for 1941.

They designed an aircraft system for 1945. While we were perfecting the sword, they were building the industrial age. In his final interview in 2000, Saburro Sakai reflected that the Zero made Japan a great power, but the Hellcat revealed its limits. Japanese pilots mocked the Hellcat’s heavy, clumsy design, not realizing that weight meant power, protection, and endurance, qualities Japan’s aircraft lacked.

The Hellcat embodied a nation that valued systems, industry, and survival over myth. While Japan’s aerial samurai clung to outdated ideals, America built machines that won wars. When the laughter faded, Japan’s air force was gone. And the Hellcat, the supposed joke, ended the war with a 19 to1 kill ratio. It had the last

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load