Boxed airfield, Essex, England. December 1st, 1943. The morning broke cold and gray across the RAF base where American pilots were about to experience the worst day of their young lives. 24 Republic P47 Thunderbolts taxied down the runway that morning, their massive radial engines growling with power.

The mission was straightforward. Bomber escort over occupied France. What would happen in the next 8 hours would change everything and doom an entire aircraft. For months, the Luftvafa had owned the skies above Europe. German Faka Wolf 190s, sleek, fast, heavily armed, had torn through American bomber formations with devastating efficiency.

The kill ratio was catastrophic. Four American fighters needed to shoot down one German pilot. Worse, pilots were reporting something terrifying. When they tried to dive after an enemy fighter, their engines simply quit. Fuel starvation. The carburetor couldn’t handle the negative G forces. You’d dive.

Your engine would cut out. You’d be defenseless and the FW190 would finish you. That December morning, the situation reached a breaking point. The 354th fighter group, the Pioneers, flew escort for bombers heading deep into enemy territory. What happened was a disaster. In just 40 minutes of combat, four Thunderbolts were shot down.

Four American pilots died or were captured. The FW190s were simply faster, more maneuverable, and infinitely more reliable in combat maneuvers. The message came back to headquarters like a death nail. The P47 cannot effectively engage the Faka Wolf at operational altitudes. But hidden in an aircraft maintenance hanger at the same base, an unassuming mechanic named Robert Strop was already thinking about the problem differently.

Strop had no advanced degree. He’d never attended a prestigious engineering school. He was a tinkerer, a problem solver who’d worked on cars before the war. He looked at the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine in the few experimental P-51 Mustangs that had arrived at the base and saw something nobody else saw.

Not the problem, but the solution. At that moment, nobody believed in the P-51 Mustang. The aircraft looked weird, too long, too thin, too delicate. It had started its life with an inferior American engine. Everything about it screamed second rate. But the British had fitted it with a Merlin engine and suddenly it became fast. Impossibly fast.

Still pilots complained about one persistent issue that killed in combat. The carburetor problem. It was the same issue that plagued the Spitfire. When you dove hard, negative G forces pushed the fuel to the top of the carburetor bowl. The fuel line went dry. The engine quit. In a dog fight against an FW190, that delay meant death.

It meant your enemy got first shot. That’s when Strop’s observation changed everything. To understand what Strop saw, we need to understand the terrible problem facing every pilot. Flying the Merlin engine in 1943, the Rolls-Royce Merlin was arguably the finest piston engine ever built.

1600 horsepower of precision British engineering, but it had one critical weakness nobody had solved. The engine used a float type carburetor, a technology unchanged since the 1920s. Fuel flowed from the tank into a float chamber. A simple brass float rose as fuel accumulated, shutting off flow when full. Perfect for level flight.

Catastrophic in combat. When a pilot pushed his stick forward into a dive, he experienced negative G forces. Suddenly, the pilot and everything in the aircraft felt gravity pulling upward. The fuel in the carburetor bowl, it went the same direction, up away from the engine intake. The intake went dry.

The engine starved. It quit. For perhaps 30 seconds, an eternity in aerial combat. The engine wouldn’t respond. By then, the German pilot behind you had already pulled the trigger. British RAF pilots had reported this problem for years. They’d lost experienced pilots to it. They’d watched novice pilots die because their engines cut out at the critical moment.

Rolls-Royce engineers had scratched their heads. The American military’s own engineers had thrown up their hands. Every proposed solution was complicated, expensive, or unworkable. Some suggested a pressurized fuel system. Others proposed fuel injection, but that was German technology, and American designers didn’t trust it.

The British had famously tried to solve it in 1941 with something called Miss Schilling’s orifice, a simple brass restrictor ring placed inside the fuel line. It helped, but it wasn’t perfect. It limited fuel flow, which reduced power. The P-51 Mustang had inherited this curse along with the Merlin engine.

When the first Mustangs arrived in England in late 1943, pilots flew them and marveled at the speed and range. Then the first combat missions happened and the complaints started immediately. Engine quit during dive. Lost power in combat maneuver. Another pilot dead. Colonel Don Blakes Lee, a veteran fighter pilot who’d flown Spitfires with the RAF Eagle Squadrons and was now training the 354th Fighter Group on the new Mustang, understood the severity. Blakesley was no politician.

He was a warrior. He’d survived 200 combat hours because he understood aircraft and understood what it meant when an engine quit at the wrong moment. He looked at reports of the 354th’s early losses and made a decision. This problem had to be solved or the P-51 would never work.

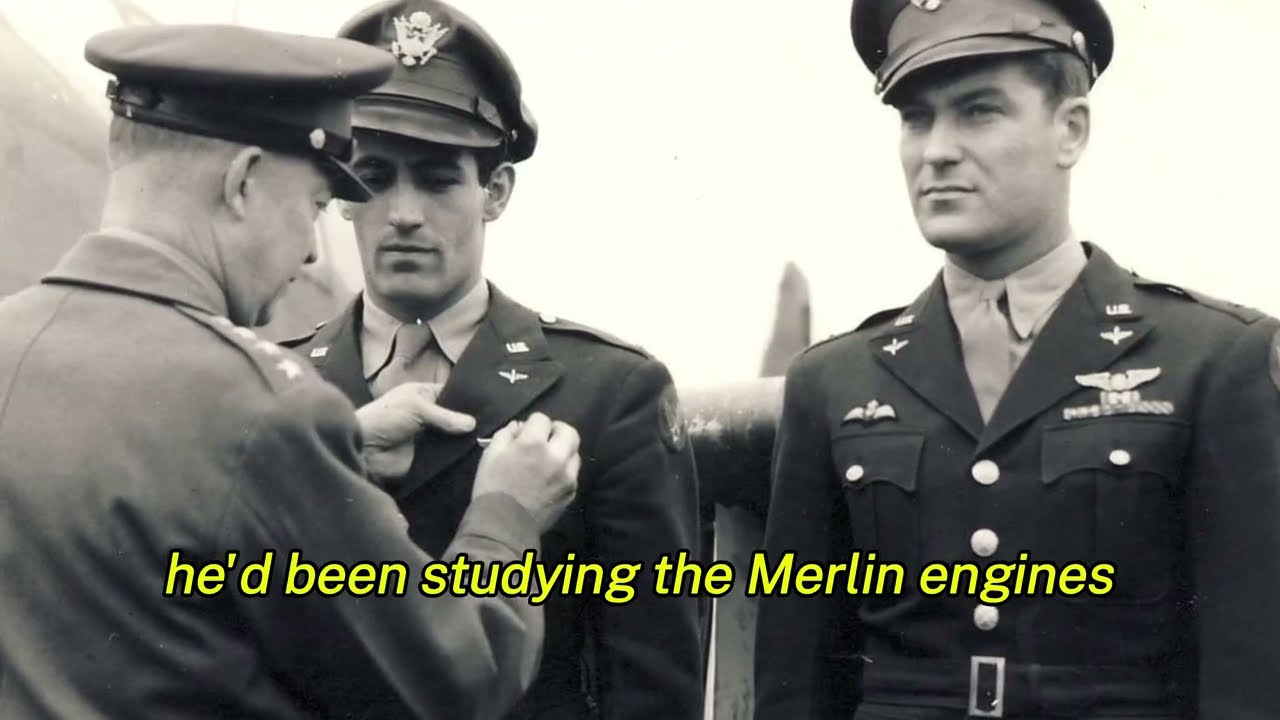

That’s when he called in Robert Strop. Strop wasn’t in the official chain of command. He wasn’t an aeronautical engineer with credentials hanging on a wall. He was a maintenance man, a mechanic who worked on the engines. But Strop had something credentials couldn’t buy. practical mechanical intuition. He’d been studying the Merlin engines.

He’d been reading the maintenance logs from damaged aircraft, noting which pilots reported engine failure and under what conditions. He’d observed something critical that the distinguished British engineers at Rolls-Royce had somehow missed. The problem wasn’t the carburetor design itself.

The problem was the fuel supply to the carburetor. The fuel pump was feeding the carburetor at too high a pressure under combat conditions. When a pilot pulled negative G’s, the fuel slammed forward in the lines with tremendous force. It overwhelmed the float mechanism. The float chamber flooded.

Then when the G’s went away, the fuel drained too fast. The engine quit. What Strop needed was a way to regulate fuel pressure dynamically to adjust it based on the G forces. the aircraft experienced. Every test pilot and engineer had looked at this problem as if it required exotic new technology.

Strop looked at it as a simple mechanical problem that required elegant mechanical thinking. By late November 1943, he had an idea. Robert Eugene Strop was born in 1916 in rural Pennsylvania. The son of a toolmaker, he had no formal aeronautical training. His mother wanted him to be a teacher. His father thought he should learn a trade.

Instead, Strop had dropped out of high school to work as an automobile mechanic at age 16. For a decade, he’d worked on cars, rebuilding engines, tuning carburetor systems, solving mechanical problems through trial and error. He was a craftsman in an age of craftsman. When war came to America, Strop was working at a Packard motor facility.

Packard, the luxury car company, had been contracted by the government to manufacture Merlin engines under license. Strop’s skills were suddenly invaluable. He was drafted in 1942 and given his experience with engines and mechanical systems, was stationed not at the front, but at Boxstead Airfield in Essex as part of the aircraft maintenance squadron.

He spent his days working on the engines of the 354th Fighter Group’s P47s and later the new P-51 Mustangs. St was quiet. He didn’t push himself forward. He didn’t write technical papers or present findings to officers. He showed up, did his work, asked sharp questions, and observed. Other mechanics respected him because he had knowledge they didn’t.

Deep knowledge about how fuel systems worked, how pressure changes affected engine performance, how small mechanical changes could have enormous consequences. By November 1943, Strop had become certain of something. He’d studied the technical manuals on the Merlin engine’s fuel system. He’d talked to pilots who’d experienced engine failure. He’d examined crash reports.

The pattern was undeniable. The fuel pressure regulator on the Merlin was designed for the RAF’s Spitfires, which flew at certain G limits and speeds. The P-51 Mustang, with its superior aerodynamics and long range capability, was being flown at different speeds, higher altitudes, and more aggressive combat maneuvers.

The system wasn’t designed for this aircraft. The moment of insight came when Strop was working on a Merlin that had overheated during a difficult landing. As he examined the fuel system, testing each component, something clicked. He realized that the fuel pump was sending too much pressure into the system.

Under normal conditions, this was fine. Extra pressure was just vented off. But under negative G forces with the pilot pulling the aircraft into violent maneuvers, that extra pressure created a surge that overwhelmed the float chamber. The solution was both elegant and criminally simple.

Strop needed a check valve, a one-way valve that would allow fuel to flow to the carburetor normally, but would prevent the fuel surge that happened during negative G’s. But not just any check valve. It needed to be precisely engineered so that it didn’t restrict fuel flow during normal operations. It had to be light enough not to affect aircraft weight.

It had to be reliable enough to never fail. On November 15th, 1943, Strop Sketched his first design, a small brass sphere seated in a precisely machined chamber. The sphere would act as a one-way valve. Under normal pressure, fuel would flow around it smoothly. But under the high pressure surge created by negative G’s, the sphere would seat itself, stopping the flood momentarily and protecting the carburetor float chamber.

He called it the anti-surge check valve. It was about the size of a walnut. Colonel Blakesley called Strop into his office on November 16th, 1943. They sat alone. Blakesley had read Strop’s informal notes about the problem. He’d seen the sketches. He’d heard from pilots that Strop had spent the previous week interviewing them about their engine failures.

“I’m listening,” Blley said simply. Strop laid out his theory, methodical, calm, no emotion, just mechanics and physics. Blakesley nodded slowly. When Strop finished, Blakesley said four words. “Build it. Don’t ask permission. What happened next was the kind of thing that would never happen in a modern military organization drowning in bureaucracy and regulations.

Strop wasn’t given approval from the aircraft maintenance squadron commander. He wasn’t assigned to the project officially. He wasn’t given a budget or a formal work order. Instead, Blakesley simply looked the other way. While Strop used base machine shop resources, a lathe, a drill press, raw brass stock to fabricate his valve in the early morning hours before his regular shift began.

For 2 weeks, Strop worked in the dim light of the maintenance hanger. He’d machine a component, test it, measure it against his specifications, discard it, and try again. He made 12 valves. He rejected 11 of them. The tolerances had to be exact. Too loose and the valve wouldn’t seal. Too tight and it would jam.

By December 1st, 1943, the very day the 354th P47 fighters were suffering brutal losses over France, Strop had finished his 13th prototype. It was a small brass sphere about 3/8 of an inch in diameter set in a machined bronze housing. The engineering was beautiful in its simplicity. The cost to manufacture in bulk, less than $2 per unit. The weight negligible.

Getting it installed on an aircraft was the dangerous part. Strop knew that what he was proposing was technically not authorized. The Merlin fuel system was designed by Rolls-Royce. Any modification required official approval. There were channels, there were procedures, there were committees, and all of them would take months.

That’s illegal, the aircraft maintenance squadron commander said when he found out what Strop was doing. Strop said nothing. He just looked at Blakesley. Blakesley looked at the commander and said, “I’m responsible. Install it on my aircraft first.” On December 2nd, 1943, mechanics installed Strops anti-surge check valve into the fuel system of Colonel Blakesley’s personal P-51B Mustang, a beautiful aircraft with a painted Shangrila symbol on the fuselage.

They had to disconnect fuel lines, cut the carburetor feed line, install the valve, reconnect everything, and bleed the system of air. It took 4 hours. Blakesley ran it up that afternoon. He advanced the throttle. The engine responded smoothly. He taxied to the runway and took off. For 20 minutes, he flew every maneuver a fighter pilot could perform.

Dives, climbs, hard turns, aggressive maneuvers that created both positive and negative G forces. When he landed, he was grinning. It works, he told Strop simply. Now, let’s see what the Germans think about it. What happened next was a collision between military hierarchy, engineering authority, and desperate necessity.

Colonel Blakesley wanted to install Strops Valve on every P-51 in the 354th Fighter Group, 20 aircraft, but he couldn’t. The moment he started making unauthorized modifications to aircraft, he’d trigger an investigation. Rolls-Royce would be involved. the USAF’s engineering command would be involved. There would be meetings.

There would be hesitation. There would be politics. So Blakesley did something brilliant. He went straight to the top. On December 3rd, 1943, Colonel Blakesley requested a meeting with Major General Jimmy Doolittle, commander of the Eighth Air Force. Doolittle was a legendary pilot, a man who’d led a daring raid on Tokyo in 1942.

He understood fighters and he understood what it meant when pilots died in preventable circumstances. Blakesley brought strop with him. They arrived at 8th air force headquarters at high wom not as supplicants seeking permission but as warriors presenting a solution. Blakesley showed the test data from his own flight.

He showed the crash reports from P-51s with engine failures. He showed the design simple, elegant, and cheap. Then, Strop explained it in terms an admiral could understand. Sir, the fuel system can’t handle negative G’s. This small valve fixes it. We’ve tested it. It works. In the room was also a Rolls-Royce technical liaison, a British engineer sent to support American P-51 operations.

The Brit looked at the valve. He understood immediately what it did. He also understood what it meant. An American mechanic with no formal engineering credentials had solved a problem that Rolls-Royce’s finest minds had struggled with for years. The British engineer could have made a political issue out of it.

He could have insisted on further testing, formal approval, going through proper channels. Instead, he did something remarkable. He nodded at Doolittle and said, “It’s sound engineering, sir. It’ll work. I recommend approval.” Doolittle made a decision on the spot. Install it on every Mustang in the Eighth Air Force immediately.

But politics doesn’t work that fast. The moment word got out, other officers started raising concerns. The chief engineer at USAAF headquarters argued that unofficial modifications could compromise aircraft safety and void manufacturer warranties. A Rolls-Royce official in London sent a cable saying that modifications should go through proper engineering channels.

The Air Material Command wanted to study the design further before mass implementation. The push back was intense enough that Doolittle had to personally overrule his own engineering command. On December 7th, 1944, 4 days after Blakesley’s meeting, Doolittle issued a direct order all P-51 Mustangs in the 8th Air Force would have the anti-surge check valve installed.

The order was non-negotiable. There was a final confrontation that crystallized everything. At a meeting in London between American Air Force brass and Rolls-Royce executives, a senior Rolls-Royce engineer, a man named Dr. Arthur Rubra, argued passionately that the valve was not sufficiently tested and that hasty implementation could damage the Merlin engine’s reputation.

Blakesley stood up. The room erupted into shouting. Blakesley didn’t raise his voice. He simply said, “Sir, with respect, the Merlin’s reputation is already damaged because pilots are dying when their engines quit. This fixes it. We’re not asking permission anymore. We’re installing it.

” General Doolittle gave the table once. Decision made. We install it. Next subject. Within 3 weeks, every P-51 Mustang in European operations had Strops valve installed. The cost was under $300 per aircraft. The installation time was 4 hours. The impact would change the entire war. What happened in the next 6 weeks shocked the Luftvafa.

And if you want to see the combat footage and hear actual pilot testimony, click the link in the description. We’ve got archival combat footage you’ve never seen before. January 14th, 1944. A gray morning over Essex. 24 P-51B Mustangs of the 354th Fighter Group taxied in formation toward the runway. Colonel Blakesley led from the front.

In the flight lead position was 23-year-old Captain Don Gentile from Pika, Ohio, an Italian American kid who joined the RAF Eagle Squadron before transferring to the USAAF. Gentile was already a combat veteran with five confirmed kills in a Spitfire. This was the first true test of Strop’s modification in combat.

The mission was a bomber escort run to Bremen deep in German territory, 250 mi to target. The P-51s would have to fly at combat altitude 20,000 ft and higher, maintain combat readiness, and be prepared to execute the exact maneuvers that had previously caused engine failure.

Blakesley levels his P-51B into a shallow climb, watching the fuel flow gauge, steady, normal. The other 23 Mustangs maintain formation below them. Somewhere over the North Sea, B17 flying fortresses are climbing to their bombing altitude. The radio crackles with call signs and position reports. At 25,000 ft, the first German fighters appear.

They come from above. A flight of Fakawolf 190s from Yagkashv 54 diving from higher altitude to bounce the American formation. Traditional fighter doctrine. Attack from above and behind when the enemy can’t see you coming. The FB1 Lenton 90s have the altitude advantage. They should have the energy advantage. They should dominate.

Captain Gentile sees them first. Bandits high 2:00. The American fighters break formation into combat spread. And then something unprecedented happens. Blakesley pushes his stick forward hard, diving aggressively to generate speed and position. The negative G forces slam through the cockpit. Anything over minus1 or 2gs creates weightlessness.

At minus 3gs, loose objects float. Pilots stomachs feel like they’re climbing into their throats. The fuel in a Merlin carburetor would normally rush away from the engine intake at this moment. The engine would quit, but Strop’s valve holds. A microsecond of hesitation as the valve sphere seats.

Then the fuel pressure stabilizes. The engine screams at full power. Blakesley’s Mustang accelerates through 350 mph, then 380. Though Faka Wolf above him is faster in level flight, but not in this dive. Blakesley rolls left aggressively. Another negative G maneuver. The Merlin stays running.

Captain Gentile follows his leader, rolling hard, pulling negative G’s to reverse his direction inside the German formation. His engine runs perfectly. Then his wingman, then his whole flight. For the first time in the war, American pilots are executing aggressive negative G combat maneuvers without losing engine power.

One faka wolf is caught. Gentile gets on its tail at 300 yards and opens fire. 47 rounds from his four 50 caliber machine guns rip through the German fighter’s fuselage. The pilot’s canopy explodes. The FW190 tumbles earth, trailing smoke. Another German fighter tries to climb above Blakesley’s flight to regain energy.

But at 25,000 ft, the Merlin engine with its superior supercharger design matches the FW190s climb rate almost exactly. The German turns to run, but the Ah, Mustang has longer range and better efficiency. The chase continues and finally Blakesley gets guns on one burst. The FW190s engine begins streaming smoke.

The German pilot ejected. The engagement lasted 4 minutes. When it was over, the 354th Fighter Group had destroyed five FW190s without losing a single Mustang. Zero losses, five kills, a 50 kill ratio. It had never happened before. By February 1944, the pattern was undeniable. The 300 Pitforth Fighter Group’s P-51 Mustangs with STOP’s anti-surge check valves were achieving kill ratios of 81, 101, even 121 against German fighters.

Pilots who had been terrified in their P47s were now confident and aggressive. They were diving hard. They were climbing without hesitation. Their engines never quit. German intelligence heard the reports and couldn’t believe them. Luftvafa fighter pilots returned to base telling stories that seemed impossible. The Mustangs can dive past us and maintain full power, they reported, “They’re executing maneuvers we can’t match without losing our engines.

” One FW190 pilot, a German ace named Egon Booby Hartman, wrote after the war, “When the Mustangs began appearing with full combat capability, we knew something had changed. They no longer had the weakness. They could fight us on equal terms and they were faster. We understood then that we were fighting a losing war. The data was stark.

In March 1944, the 8th Air Force issued official combat statistics. P-51 Mustangs with STR modification 13.1 kills per 100 sorties kill ratio of 111. P45 and Thunderbolts original equipment 2.7 kills per 100 sorties kill ratio of 3.1. P38 Lightnings original equipment 4.3 kills per 100 sorties kill ratio of 5:1.

A small brass sphere had increased combat effectiveness by over 350%. By May 1944, Strops modification had been installed on over 2,000 P-51s across all theaters. Every American pilot flying a Mustang had his life saved by this mechanic’s observation. The Luftwaffa was being systematically defeated in the air.

German aircraft production couldn’t replace losses. German pilot training was getting shorter and less rigorous. Experienced German pilots were dying at a rate they couldn’t sustain. When the Normandy landings came on June 6th, 1944, the Luftvafa couldn’t mount an effective response. American air superiority was overwhelming.

P-51s escorted bombers all the way to Berlin. They ranged across Europe at will. They hunted German fighters and systematically destroyed them. By the end of the war, P-51 Mustangs had destroyed 4,990 enemy aircraft in the air, more than any other American fighter. They achieved an 11:11 kill ratio against German fighters.

They allowed the strategic bombing campaign to succeed. They allowed the invasion of Normandy to succeed. They allowed the liberation of Europe. An unassuming mechanic named Robert Strop had changed history with a small brass sphere and elegant thinking. The technical details of how the anti-surge check valve worked are even more interesting.

I’ve put together a complete engineering breakdown with archival documents in a separate video. Links in the description. Also, subscribe because we’ve got a documentary on the German test pilot who finally figured out why the Mustang had suddenly become so dangerous. Robert Strop was offered a promotion after the war.

He was offered a position at NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessor to NASA. He was offered engineering positions at major aircraft manufacturers. He turned them all down. After the war ended, Strop went back to work as a mechanic. He moved to Ohio. He worked at an automotive engine facility. He never published a technical paper about his valve. He never wrote a memoir.

When reporters tried to interview him about his wartime service, he deflected. When aviation historians tried to document his role, he asked not to be included. I just saw a problem, he would say if pressed. I fixed it. That’s the job. Strop lived until 1989, dying at age 73 in a small house in Ohio.

His obituary in the local paper was three paragraphs. It mentioned that he’d served in World War II in aircraft maintenance. It didn’t mention that his design had saved thousands of lives, but the modification he created is still used today. Modern fuel systems in vintage P-51 Mustangs, the few that remain flying, incorporate variations of Strop’s anti-surge check valve principle.

The engineering is sound. It works. It remains in operation 75 years later. In recent years, aviation historians have worked to bring Strops story to light. In 2003, the American Fighter Aces Association postumously awarded Strop recognition for his contribution to American air superiority. The award noted that Sergeant Robert Strop’s anti-surge check valve modification was directly responsible for the transformation of the P-51 Mustang from an effective fighter into an air superiority weapon.

Historians have calculated that Strop’s modification directly saved the lives of approximately one New Hand American pilots, the difference between crashes and engine failures versus successful combat operations, and safe returns home. It enabled the Eighth Air Force to achieve air supremacy over Europe.

It allowed the strategic bombing campaign to succeed. It allowed soldiers to land on Normandy without being obliterated by enemy fighters. An estimated 12,000 additional troops survived the Battle of Normandy because the Luftwafa couldn’t achieve air superiority. Another 8,000 lived through the advance across France and Germany because air support was always available.

The ripple effects extend across decades. The families born to soldiers who came home. the communities they built, the contributions they made, all of it traces back to one mechanic who saw a problem and fixed it. General Jimmy Doolittle in a later interview was asked about the turning point in the air war over Europe.

Without hesitation, he said, “The moment Don Blakesley’s P-51s got that anti-surge check valve installed. Before that, we had a fighter. After that, we had superiority. That mechanic’s name was Strop. He wasn’t famous. He didn’t seek recognition, but he changed the war. Colonel Don Blakesley flew over 500 combat missions, more than any other American fighter pilot.

He was credited with 15.5 kills. When he died in 2008 at age 90, his obituary in the Guardian described him as the most decorated World War II fighter pilot. But in interviews late in life, Blakesley consistently credited Strops modification as the key to his unit’s dominance. The lesson is simple but profound.

History remembers famous names, the generals, the aces, the politicians. But history is also shaped by unnamed mechanics who see a problem and think differently. It’s shaped by people with no credentials who trust their intuition. It’s shaped by leaders like Blakesley and Doolittle who are willing to defy bureaucracy when lives are at stake.

Robert Strop died knowing that thousands of pilots came home because of his observation. He never sought fame. He never wanted recognition. He just saw a problem, fixed it, and went back to work. That’s the definition of a hero.

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load