July 14th, 1944. Camp McCain, Mississippi. The air hung thick and wet like a wool blanket soaked in heat. Through the chainlink fence, a 13-year-old boy in a threadbear vermached uniform stood frozen. His hands trembled. His breath came shallow and quick. Across the dirty yard, black American soldiers laughed and threw a ball in wide arcs.

The boy had been taught these men were monsters. Now, one of them was walking toward him. Before we continue, if you’re enjoying this story, hit that like button and subscribe so you never miss another untold chapter of history. Drop a comment and tell us where you’re watching from. Now, let’s get back to the story.

The boy’s name was France Hartman. He had lied about his age to join the Hitler Youth Combat Unit in 1943. By spring of 1944, he was carrying a rifle in Normandy. By summer, he was a prisoner of war in the deep south of America. Everything he had been told about the world was about to unravel. Not through propaganda, not through punishment, but through a simple act of kindness that should not have been possible.

And in that moment, standing in the Mississippi heat, he realized the war had lied to him about everything. The road to Camp McCain began thousands of miles away in the rubble and lies of the Third Reich. By 1944, Germany was bleeding men faster than it could replace them. The Eastern Front devoured entire divisions.

The Western Front crumbled after D-Day. Desperate, the Nazi regime began conscripting boys as young as 12 into the Vulk Stirring and Hitler Youth Combat Units. These were not soldiers. They were children handed rifles and told to die for a collapsing empire. France had joined willingly. His father was dead on the Eastern front, his older brother missing in North Africa.

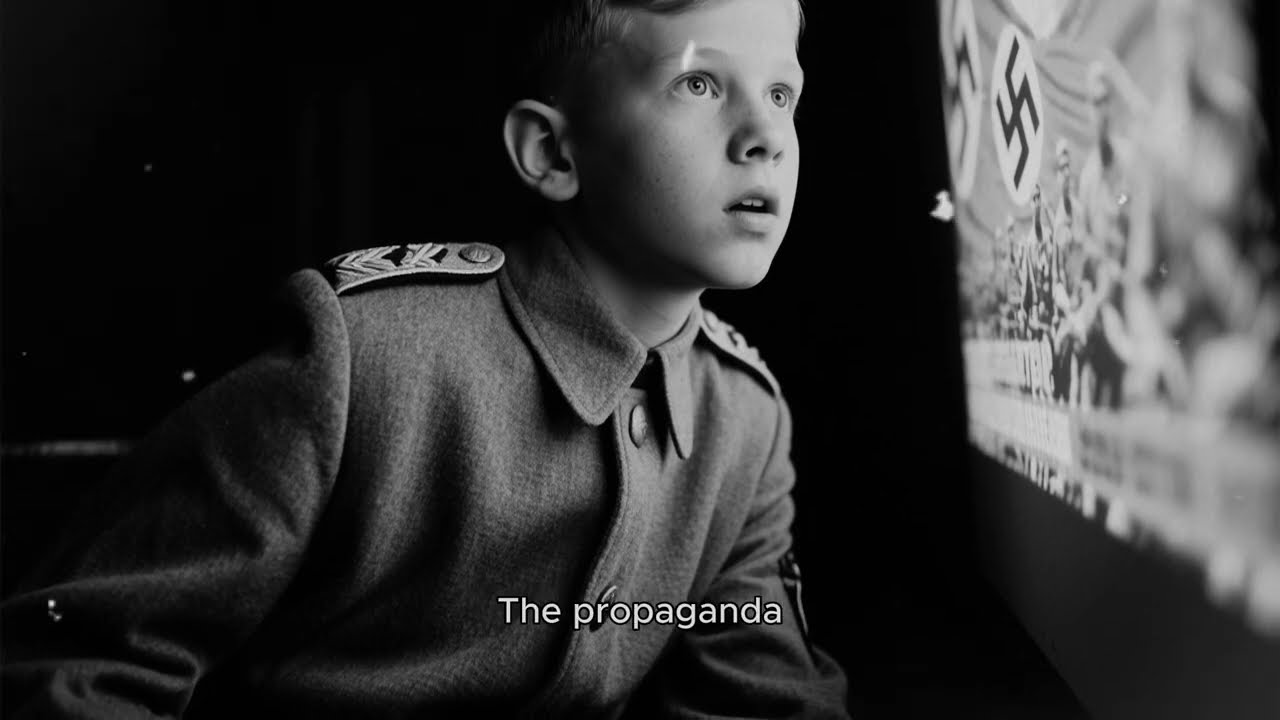

The propaganda film showed heroic boys defending the fatherland. The rallies promised glory. The teachers at school said it was every young Germans duty to fight. So France lied. He said he was 16. They gave him a uniform two sizes too big and a rifle he could barely lift. They sent him to France. He lasted three weeks.

On June 28th, 1944, his unit was overrun near St. Lei. American forces swept through in a torrent of steel and firepower. France hid in a barn. He was found by a platin of the 29th Infantry Division. They pulled him out, hands up, crying. He was shipped to a processing center in England, then loaded onto a transport ship bound for the United States.

By mid July, he arrived at Camp McCain. The camp was one of dozens across America that held German prisoners of war. Over 370,000 German Po were detained on US soil during the war. Most worked on farms or in factories under guard. They were fed. They were clothed. They were treated according to the Geneva Conventions.

For many, it was the safest they had been in years. But for France and the other young prisoners, safety was not what they feared. They feared the guards. The US Army was segregated in 1944. Black soldiers served in separate units. They were often assigned support roles, logistics, or guard duty. At Camp McCain, the military police detail assigned to guard German pose was made up almost entirely of black soldiers.

This was not an accident. The army believed German prisoners would be less likely to attempt escape if guarded by men they had been taught to view as inferior. It was a cruel irony. The very men the Nazis called subhuman were now responsible for their captivity. France had been raised on Nazi racial ideology.

In school, teachers showed charts claiming biological hierarchies. In the Hitler youth, leaders warned that black people were dangerous, violent, less than human. Propaganda films depicted them as monsters. France believed it all. He had never met a black person in his life, but he knew or thought he knew what they were.

So when he stepped off the truck at Camp of McCain and saw the guards, his blood ran cold. The first night, France barely slept. He lay on a cot in a barracks with 30 other boys and young men. They whispered in the dark. “They’ll kill us,” one boy said. “They’ll make us work until we die,” said another.

An older prisoner, a sergeant in his 20s, told them to shut up. “They’re Americans,” he said. “They follow rules, but even he sounded uncertain.” The next morning, the prisoners were assembled in the yard. The sun blazed, the humidity pressed down like a hand. A black sergeant stood at the front and read the camp rules in accented at clear German.

No fighting, no escape attempts. Work assignments would be given daily. Rations would be provided. Medical care was available. The prisoners listened in silence. France watched the sergeant’s face. It was calm, professional, human. It confused him. Over the following days, France began to notice things that did not align with what he had been taught.

The guards did not beat the prisoners. They did not starve them. They did not scream or threaten. They simply did their jobs. They counted heads at roll call. They escorted work details. They monitored the fence line. And in their downtime, they played baseball. The game was foreign to France.

He had never seen it before. But he watched through the fence as the guards threw a small white ball back and forth with leather gloves. They hid it with wooden bats. They ran and shouted and laughed. It looked like joy. It looked like something boys did in his village before the war. It looked human. On the fifth day, it happened.

One of the guards hit the ball too hard. It sailed high over the back stop over the guard tower and landed inside the prisoner compound. It rolled to a stop at France’s feet. He stared at it, his heart pounded. The guard who had hit it jogged toward the fence. He was tall, broadshouldered, with a smile that showed white teeth.

He stopped a few feet from the wire and pointed at the ball. “Hey, kid,” he called out in English. France did not understand the words, but he understood the gesture. France bent down slowly. His hands shook as he picked up the ball. It was heavier than he expected, stitched with red thread. He looked up.

The guard was still smiling. He held up his glove and mind throwing. France hesitated. Every instinct told him this was a trap, but the guard’s face showed no malice, only patience. So France threw the ball. It wobbled through the air and landed short. The guard scooped it up and gave a thumbs up.

Then he tipped his cap and jogged back to the game. That small moment cracked something open inside France. It was not much, just a gesture. But it was the first time since his capture that someone had treated him like a person. Not a prisoner, not a Nazi, just a kid who threw a ball. Over the next week, it happened again and again.

The guards began aiming their foul balls toward the fence on purpose. France and a few other boys started waiting near the wire. They would pick up the ball and throw it back. The guards would cheer or laugh or wave. It became a ritual, a game within a game. And slowly the fear began to fade. One afternoon, a guard named Corporal James Tilman walked up to the fence during a break.

He carried a baseball and a worn glove. He spoke in slow, simple English, using hand gestures to bridge the language gap. He showed France how to hold the ball for a fast ball, how to grip it for a curve. France mimicked the motions. Tilman nodded and smiled. That’s it, kid. You got it. France did not know the words, but he felt the encouragement.

Another prisoner, an older boy named Wernern, watched from a distance. He had been in the Vermacht longer than France. He had fought in Russia. He had seen terrible things. He walked over to the fence and said in German, “You shouldn’t trust them.” France looked at him. “Why not?” Wernern’s jaw tightened.

“Because that’s what they want. They want you to forget who you are.” France looked back at Tilman, who was demonstrating a throwing motion. Maybe, France, said quietly. I want to forget. The games continued. The guards set up a makeshift pitching area near the fence so the boys could practice.

They brought extra gloves and left them on the wire. The prisoners were not supposed to have them, but the officers looked the other way. It was harmless. It kept morale up, and it was working. The tension in the camp eased. The boys stopped whispering about violence in the night. They started asking the guards about America, about baseball, about life beyond the war.

France began to write letters home. The Red Cross facilitated mail between Po and their families. In his second letter, France wrote to his mother. The guards here are not what we were told. They are kind. They play games with us. One of them taught me to throw a ball. I do not understand why we were taught to hate them.

He did not know if the letter would reach her. Germany was in chaos, but he wrote it anyway. By August, France and several other boys were part of a worked detail picking cotton on a nearby farm. The labor was hard, but not cruel. They were given water breaks. They were paid a small wage in camp currency and they were guarded by the same black MPs who had played catch with them.

One day during lunch, Corporal Tilman sat down near France and shared his canteen. He pulled out a photograph of his family, a wife, two young daughters. He pointed at them and said their names. France understood. He pulled out a creased photo of his mother and sister. Tilman nodded solemnly. For a moment, they were not guard and prisoner.

They were two men far from home. Back at the camp, the games grew more organized. The guards set up a real game one Sunday afternoon and invited the prisoners to watch. Some even let them join in for a few innings. Fran stood in the outfield, glove on his hand, and felt the sun on his face. He heard the crack of the bat.

He saw the ball arc through the sky. He ran, caught it, and threw it back. The guards cheered. So did the other prisoners. For a few hours, the war disappeared. But the world outside the fence had not stopped. News filtered into the camp through guards and red cross updates. The Allies had broken out of Normandy.

Paris was liberated in late August. Soviet forces pushed deeper into Eastern Europe. Germany was being crushed from both sides. The prisoners knew it. They saw it in the guards faces. They heard it in the camp commander speeches. The war was ending and Germany was losing. France lay awake one night in September staring at the ceiling.

He thought about his time in France, the fear, the chaos, the moment he was captured. He thought about the propaganda films, the speeches, the promises of victory. All of it had been a lie. And yet here in this camp, surrounded by men he was taught to fear, he felt safer than he ever had in uniform. He felt seen.

It made him angry. It made him sad. It made him wonder what kind of country he had been fighting for. One evening, Corporal Tilman approached the fence after roll call. He carried a letter. He handed it to France through the wire. It was from the red cross. France opened it with shaking hands. It was from his mother.

She was alive. His sister was alive. They were in a refugee center in Bavaria. The house was gone, destroyed in a bombing raid. But they were alive. France read the letter three times. Tears blurred the words. Tilman stood quietly on the other side of the fence. When France looked up, Tilman nodded.

“Good news?” he asked in English. France did not understand the words, but he smiled and nodded. Tilman smiled back. By October, the lessons of the baseball games had spread throughout the camp. Other guards and prisoners began interacting more openly. There were still rules. There was still offense.

But the hostility had dissolved. The boys no longer saw monsters. They saw men. Men who missed their families. Men who laughed and joked and played games. Men who treated them with dignity. An older German officer, a captain in his 40s, approached France one afternoon. He had been watching the games from a distance.

He said in German, “You know this doesn’t change anything. We’re still enemies.” France looked at him. “Are we?” he asked. The captain frowned. “Of course. They’re holding us prisoner.” Fran shook his head. “They’re keeping us alive. That’s more than our own army did.” The captain walked away, but Fran saw doubt in his eyes.

In November, the prisoners were allowed to form a soccer team. They played against teams from other compounds. The guards refereed. Corporal Tilman even joined one match and played defense. He was terrible. The prisoners laughed. So did the other guards. It was absurd. It was beautiful.

It was the opposite of everything the war had been. France received another letter in December, this time from a cousin who had been stationed on the Eastern front. The letter was brief and grim. The Red Army was closing in. Cities were burning. Soldiers were surrendering in droves. The cousin wrote, “There is no Germany left to fight for. Only survival.

France folded the letter and put it in his pocket. He walked to the fence and stared out at the Mississippi sky. It was wide and clear and endless.” He thought about his cousin, about his mother, about all the boys like him who had believed the lies. And he felt a deep aching gratitude that he was here, safe, alive, playing catch with men who should have been his enemies.

The final game of the season was held on Christmas Eve, 1,944. The guards organized a match between themselves and the prisoners. It was played under flood lights strung up along the fence. The air was cold for Mississippi. The prisoners wore donated jackets. The guards wore their uniforms. France pitched three innings.

He threw a curveball that Corporal Tilman swung at and missed. The guards erupted in laughter. Tilman shook his head and grinned. France grinned back. After the game, the guards brought out food, hot dogs, bread, canned fruit. It was not a feast, but it was generous. The prisoners and guards sat together in the yard, separated by a symbolic line, but united by the moment.

Someone started singing Silent Night in German. Still not. The guards did not know the words, but they hummed along. France closed his eyes and let the music wash over him. He thought about the boy he had been 6 months ago, terrified, indoctrinated, alone. That boy was gone. In his place was someone who had learned that humanity could not be destroyed by propaganda. It could only be revealed.

When the war ended in May 1945, France remained at Camp McCain for several more months. Repatriation took time. He used the time to learn English from the guards. He played more baseball. He wrote letters. And he prepared to return to a country he no longer recognized. When he finally boarded the ship home in late 1945, Corporal Tilman was there to see him off.

They shook hands through the wire one last time. Tilman said, “Good luck, kid.” France understood, he replied in halting English. “Thank you for everything,” Tilman nodded. And France walked away. Years later, France would tell his children about the camp. “Not all at once and never easily. He would talk about the heat first, how it pressed down on you until your thoughts felt slow and heavy.

He would talk about the fear, the kind that lived in your chest even when nothing was happening. He would talk about the fence, the way it cut the world in two and taught boys to believe that danger always lived on the other side. And then after a pause, he would tell them about the black soldier who taught him to throw a curveball.

He would describe Corporal Tilman’s patience, his steady voice, the way he stood in the dirt like he belonged to it, like nothing could shake him. France would say that at Camp McCain, in that moment, he learned something no one had ever taught him before, that the enemy was never the people standing across from you. It was the stories you were told about them.

The lies that built fences long before the wire ever went up. He never saw Corporal Tilman again. The war ended. The camp emptied. The world went on, indifferent to the small, fragile human moments that had unfolded within its barbed wire fences. Life moved forward the way it always does, whether you are ready or not, carrying with it the loud and quiet tragedies, the victories, the losses, and the memories we try not to hold, but can never fully let go of.

But France never forgot him. He never forgot the weight of the ball in his hand, or the quiet trust it took to throw it across that yard. He never forgot the way Tilman’s eyes had met his, steady and patient, as if the world beyond the fence did not exist, as if the only thing that mattered was the simple exchange of one person to another.

And he never stopped playing catch. Not with his children, who grew up laughing and learning without knowing the true gravity of the lesson behind the game. Not with his grandchildren, who caught and threw with the same innocence and wonder, and not with himself on quiet mornings when the air was still in the ball spun in arcs that seemed to slow time itself.

The lesson of Camp McCain was never written down. It wasn’t carved into monuments, taught in classrooms, or signed into treaties. It was too subtle, too human for official record. It lived instead in a dusty yard in Mississippi, in the memory of a boy raised on hate, who had learned, however briefly and quietly, to meet another person, not as an enemy, but as a fellow human.

It existed in the silence between throws, in the patience of one man, and the courage of another to receive trust he had not yet earned. It was a small, invisible moment, a quiet revolution that proved a simple, enduring truth. Humanity cannot be unlearned. It cannot be legislated or forced or dictated.

It can only be remembered. Sometimes all it takes is a game of catch. One throw, one pause, one quiet act of trust. And through that small gesture, the world bends just a little toward

News

Mit 81 Jahren verrät Albano Carisi ENDLICH sein größtes Geheimnis!

Heute tauchen wir ein in eine der bewegendsten Liebesgeschichten der Musikwelt. Mit 81 Jahren hat Albano …

Terence Hill ist jetzt über 86 Jahre alt – wie er lebt, ist traurig

Terence Hill, ein Name, der bei Millionen von Menschen weltweit sofort ein Lächeln auf die Lippen zaubert….

Romina Power bricht ihr Schweigen: ‘Das war nie meine Entscheidung

non è stato ancora provato nulla e io ho la sensazione dentro di me che lei sia …

Mit 77 Jahren gab Arnold Schwarzenegger endlich zu, was wir alle befürchtet hatten

Ich will sagen, das Beste ist, wenn man gesunden Geist hat und ein gesunden Körper. Arnold Schwarzeneggers…

Mit 70 Jahren gibt Dieter Bohlen endlich zu, womit niemand gerechnet hat

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen selbst die stärksten unter uns ihre Masken fallen [musik] lassen…

Die WAHRHEIT über die Ehe von Bastian Schweinsteiger und Ana Ivanović

Es gibt Momente im Leben, in denen die Fassade perfekten Glücks in sich zusammenfällt und die Welt…

End of content

No more pages to load